Notable / Recent Finds

At AHOPC we’re open to exploring the roots, influences, and parallel movements that inform poetry comics. These three notable / recent finds present poetry as art that’s sometimes outside the definition of poetry comics but still in the sphere of influence.

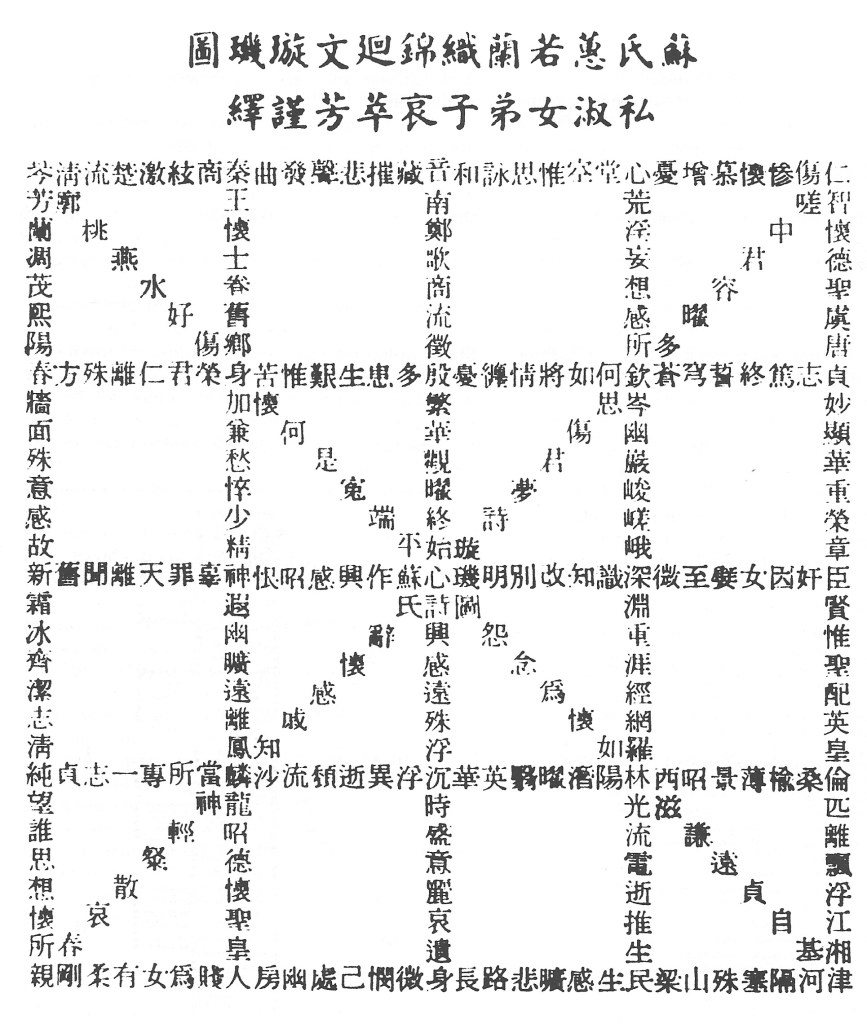

Collage has been used by both visual artists and poets alike since it’s recognition as as art form in the early 20th century. Naoko Fujimoto uses collage to create what she calls “graphic poetry,” bringing in materials that thematically underscores their meaning. Her collection “GLYPH: graphic poetry = trans. sensory” (Tupelo Press, 2021) brings both the beauty and the power of collage to the intimacy of personal poetry. In the introduction Fujimoto writes, “I wanted my graphic poems to transport the viewer’s senses from paper, bridging the gap between words and images and their physical counterparts.” She uses found materials to create a base for her poetry, which is often handwritten, sometimes cut up, and always cascaded across her canvas. Her found materials include washi, origami paper, supermarket advertisements, gift wrap, postcards, and magazines among other materials. Among my favorite poems here are “Natane Rain Is,” “Greenhouse,” and “I Burn the Upright Piano.” This is a great addition to the graphic literature canon.

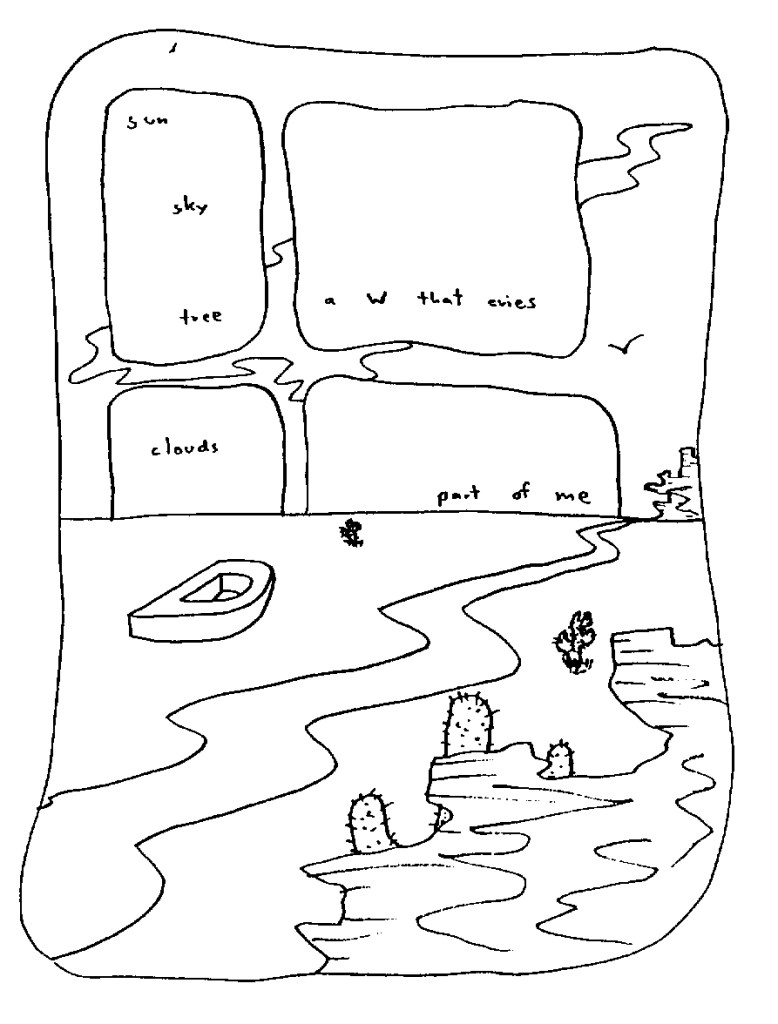

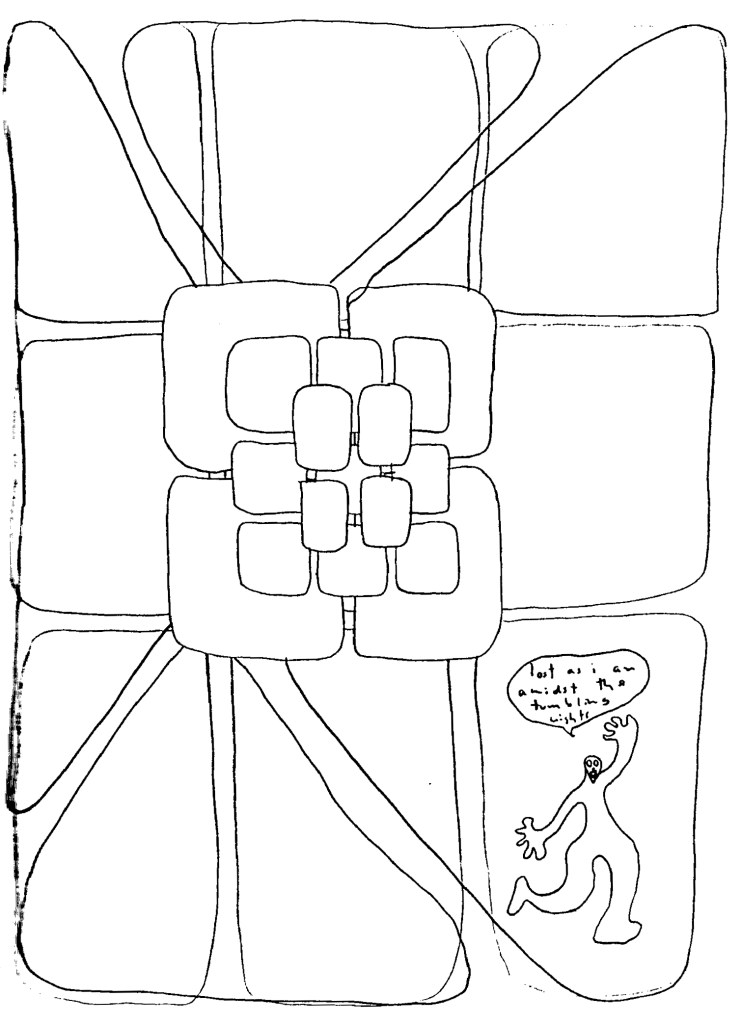

More often closer to Abstract Comics than Poetry Comics, David Lasky‘s “Manifesto Items #14: Postcard Comics” (2025) expands what can be done with the constraints of a structured format. Like fitting a sonnet into 14 lines or a haiku into 17 syllables, Lasky masters the postcard form to tell stories, illuminate poems, and expand our definnition of landscapes. He then mails them out, as he writes in the introduction, “to see if something small and precious could survive the machinery of the USPS and reach its destination.” His humor, wit (he goes meta in all the right ways), and color expertise are all on display here. For example, check out the raven’s attempt to correct Poe’s nevermore! Don’t wait to get your copy! Available here. ICYMI: I first mentioned Lasky’s “Lucky 13” a year ago in AHOPC #23. Lucky for us, he has reissued this 2023 sprawling collection of poems, comics, and poetry comics, adding some new ones and giving others more space. Full disclosure: David is my comics teacher and friend. We’ve co-curated exhibitions of haiku comics in 2024 and 2025 for art spaces in Washington and Oregon. And he’s the inspiration for this blog!

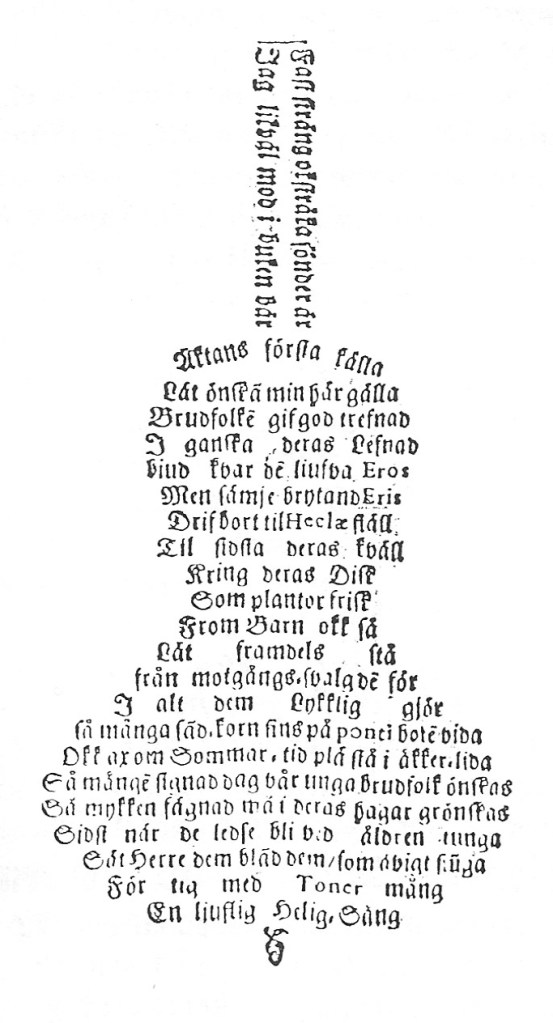

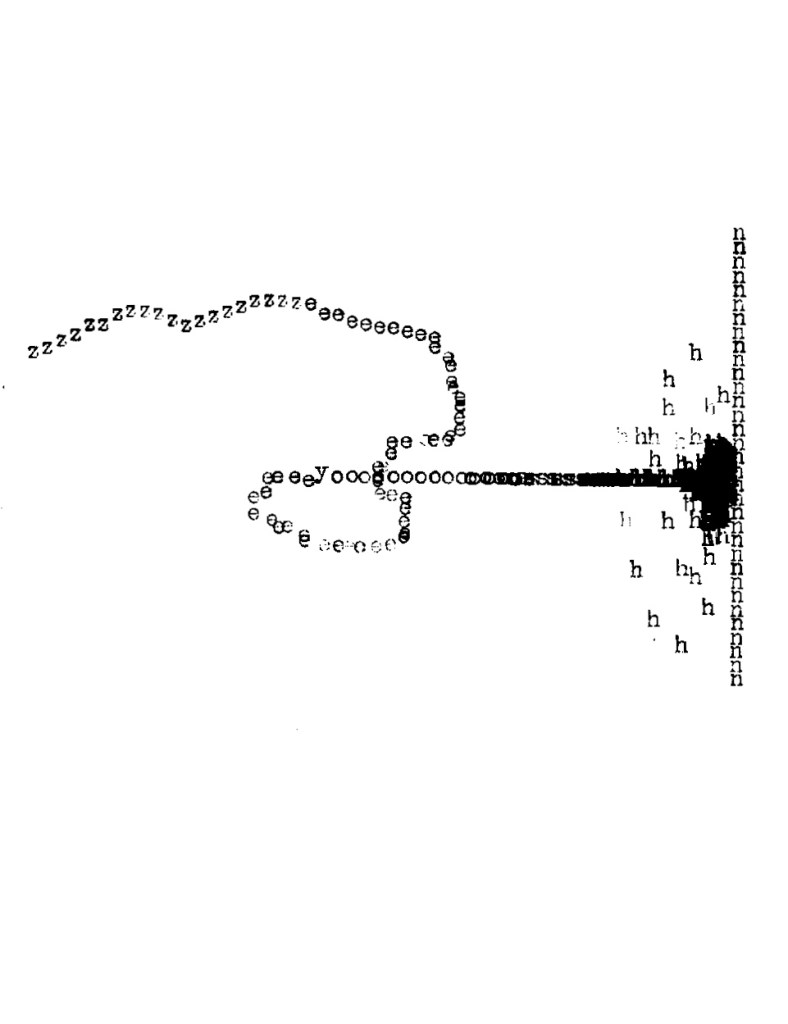

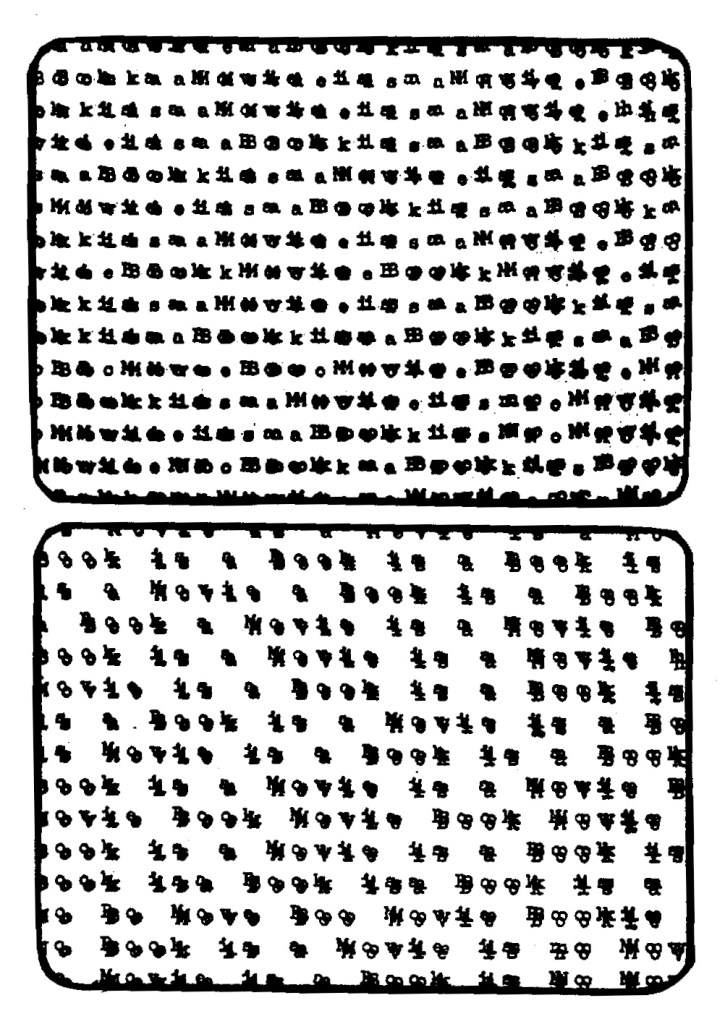

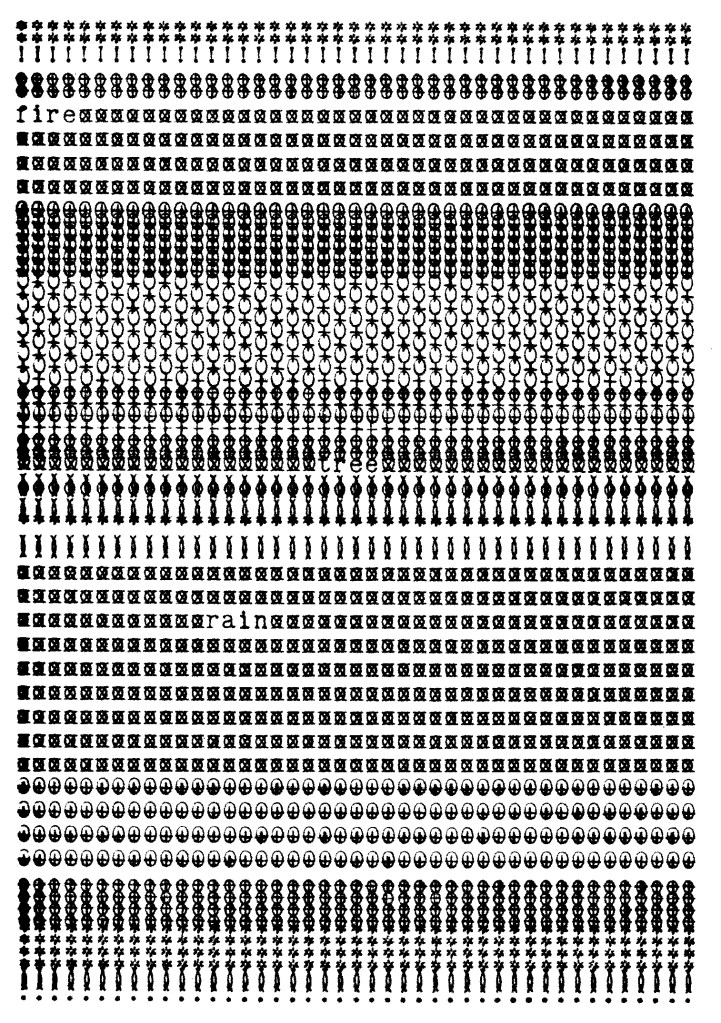

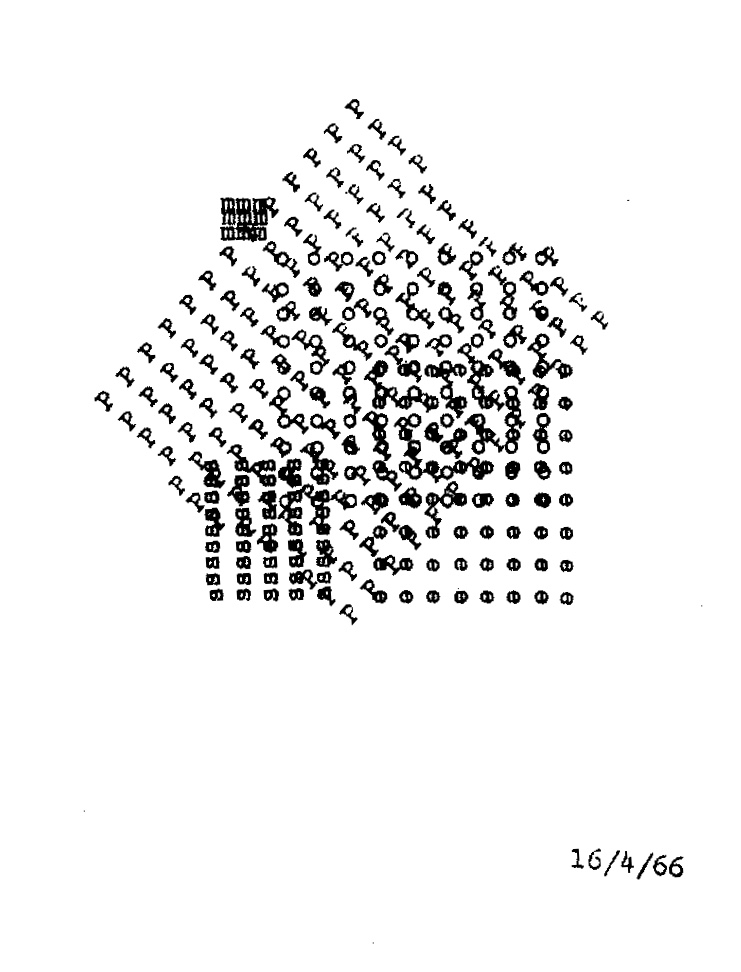

Visual poetry, as noted in AHOPC #28, is the direct descendent of concrete poetry. There’s a painterly feel to vispo that’s not always present in concrete. Poet Nico Vassilakis continues to explore and explode the power of letters to create (or should I say paint?) his poetry work “Letters of Intent” (Cyberwit.net, 2022). He notes this is “a collection of visual essays designed to explore the interior space of language material.” There’s humor (“Letters Are Escaping”); there’s instruction (“Ways To Begin”); there’s a nod to couplets (“Doubles”). The section “Opinions” sees messages emerging from the alphabet-primordial soup such as “letters are leaving these words,” “staring,” and “words are a crowd.” Like an abstract painting, I like taking my time when looking at each piece as different meanings emerge and submerge. Often layered like graffiti on graffiti, other times blended until just a color field remains, the work grabs your attention and creates wonder (a future language, perhaps?) for the reader/viewer.

Timeline: Current

Warning: This incomplete history maps my journey as a poet learning about comics and doesn’t follow a strict chronological order.