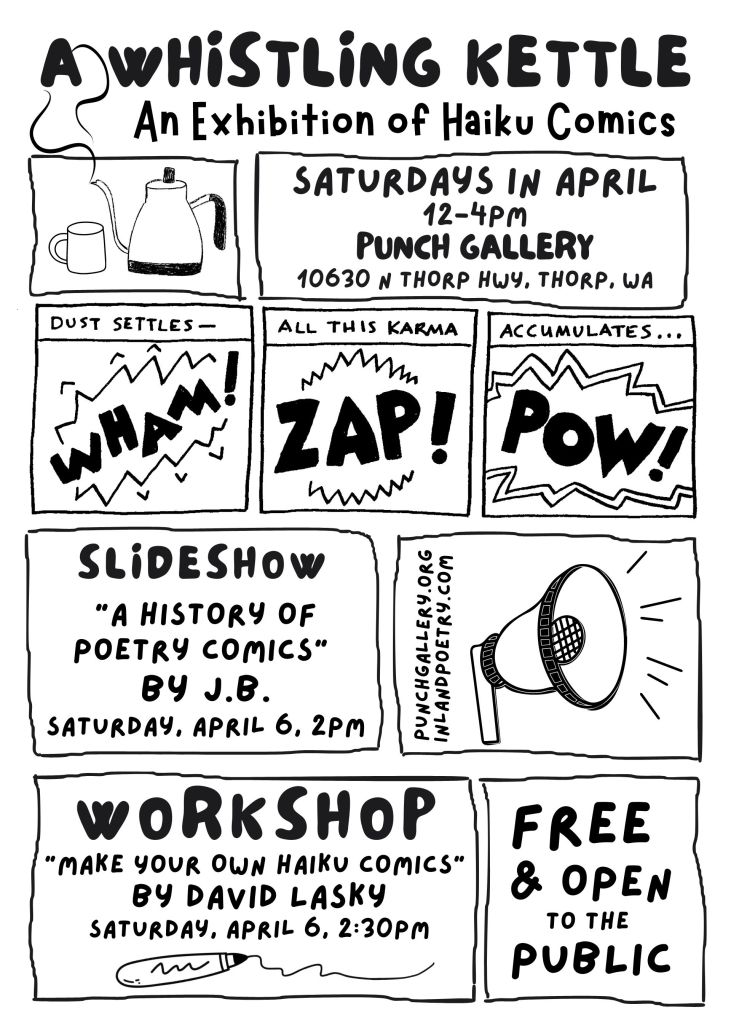

Rise in comics paralleled experimental poetry

It’s notable that concurrent with the rise in popularity and proliferation of comics in the years between about 1870 and 1920 poetry was becoming more experiemental. Possibilities for poetry were opening up, starting with how the page and text could be used to add context and illuminate meaning.

Two early (perhaps the first modern?) examples of poets experimenting with page and type are both French: Stephane Mallarme (1842-1892) and Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918).

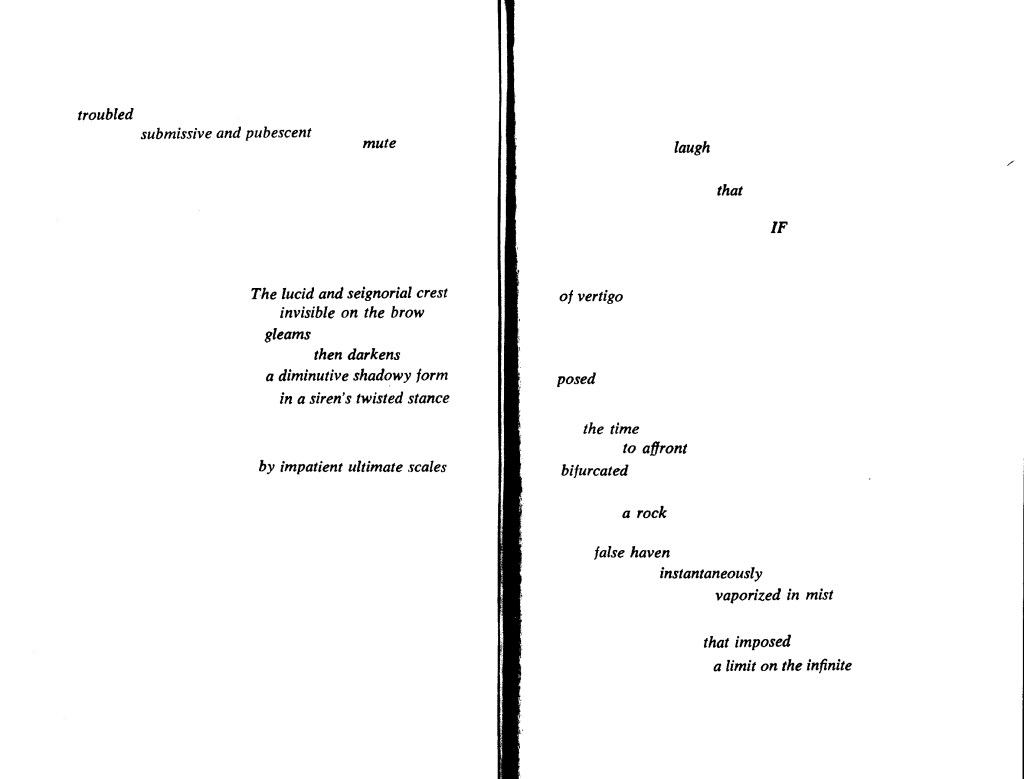

Mallarme created poems that broke the constraints of the line and the page. His late poems would run down the page, across the gutter, and even page to page. Considered a Symbolist master in France in the 1890s, Mallarme created poems toward the end of his life that were concerned with meaning and how text placement, type face, and font size could convey meaning — or at least provide graphical clues to meaning.

Here’s a two-page spread from Mallarme’s “Throw of the Dice” (1897) that illustrates the poet’s breaking with expected norms of poetry and creating what he said had “the look of a constellation.”

Apollinaire, who was influenced by the Symbolist and the more ancient pattern poetry, created poems that built on the use of the page as a canvas (as a painter would use). His calligrams left behind the linear (as in lines) of poetry, opting instead for creating meaning through graphic display of the text. He also created poems in own handwriting, which are closest to poetry comics.

Here’s an example from Apollinaire’s Calligrammes:

As a footnote, experimental poetry based on text and space became fertile ground first for concrete poetry which in turn was a forerunner of visual poetry (vispo) which continues today. See A History of Poetry Comics #10 https://punkpoet.net/2023/02/17/a-history-of-poetry-comics-10/

And BTW, in 1958 artist-poet Brion Gysin who added cut-up and collage to the poet’s toolkit, said “Writing is 50 years behind painting.” Perhaps.

Timeline: Pre-history (1897 & 1912-1913)

Warning: This incomplete history maps my journey as a poet learning about comics and doesn’t follow a strict chronological order.