Punk poet. Noisemaker. Grandpa.

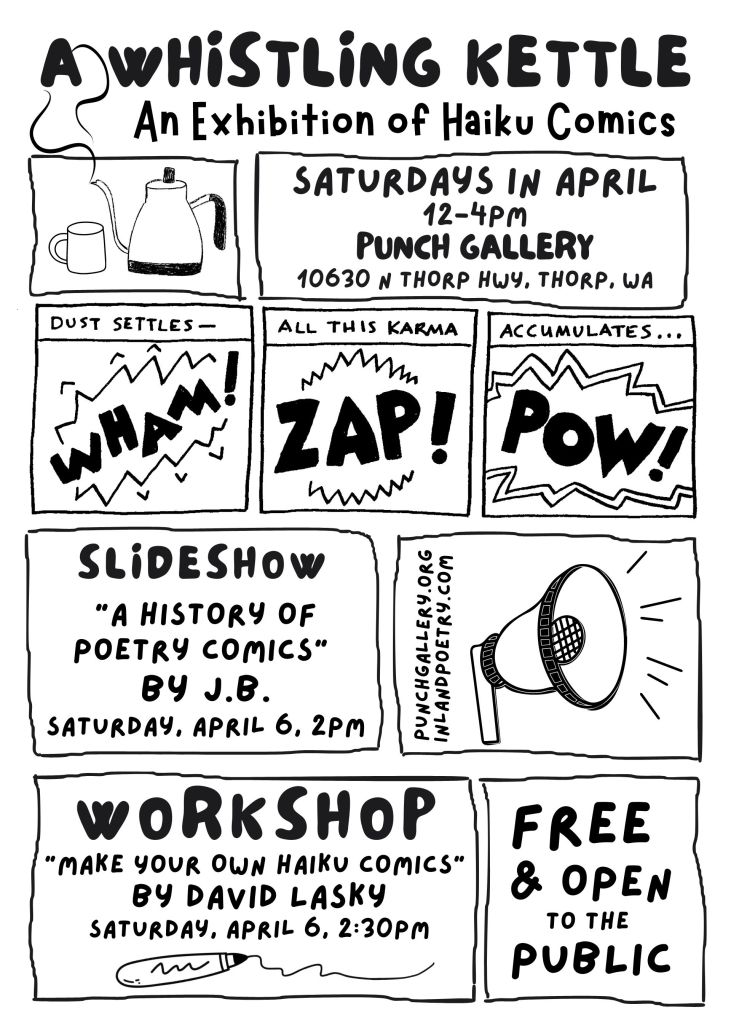

A History of Poetry Comics #25

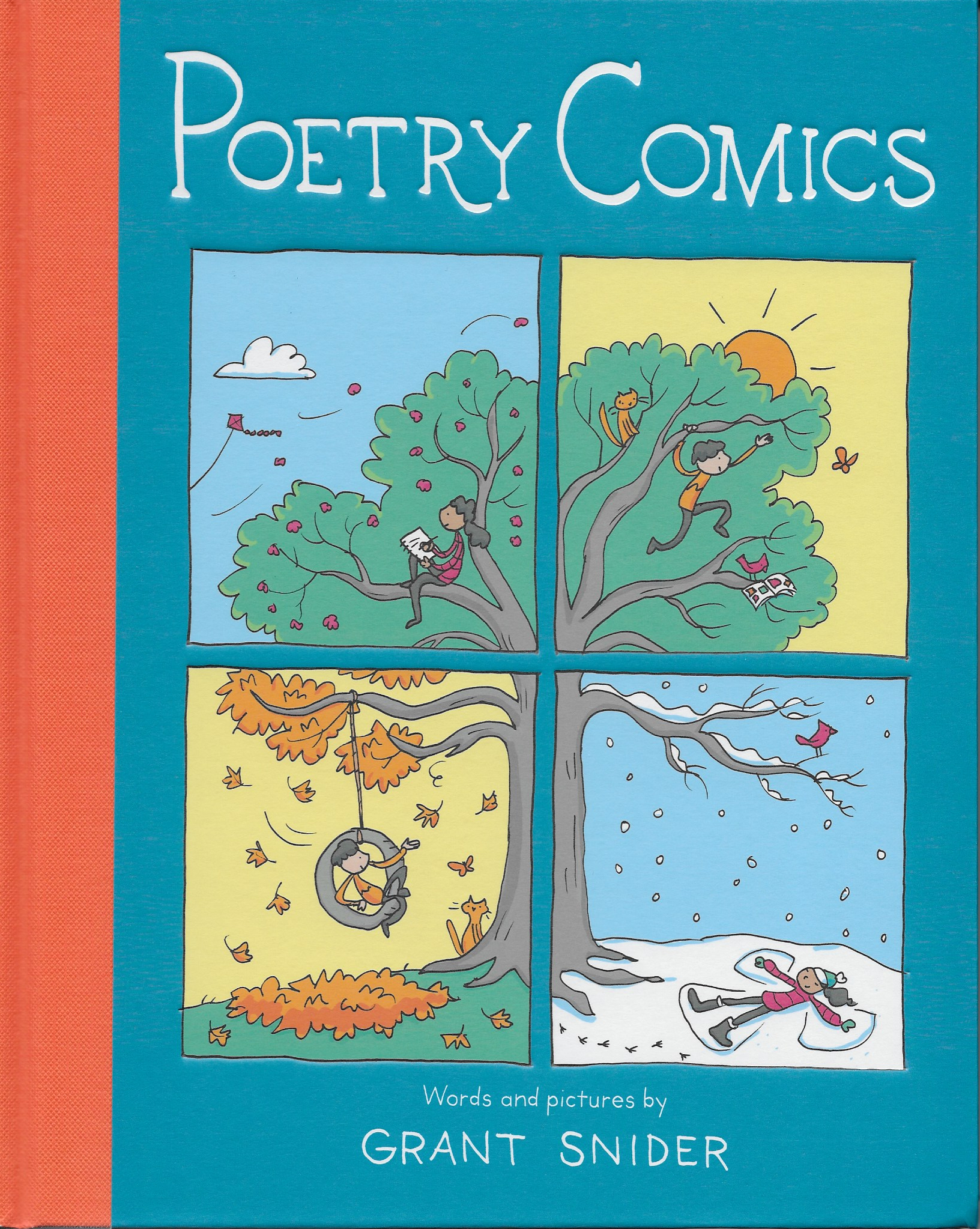

Summer Reading Book Reviews

Poetry comics continue to be a way of illuminating thoughts, adding context to text (if that isn’t redundant), and helping the reader make that leap from what is said to what is possible. Here are three poet-artists I read this summer that continue to make things new.

Puddles by Tomas Cisternas (Bored Wolves, 2024). Translated from the original Spanish, these comics by Tomas Cisternas perfectly illuminate his often spare text that focuses on nature, solitude and solace, and being human in the natural world. The work is black-and-white with a simplicity of line that matches the sentiment of the work (totally my sensibility). If you don’t want to call them poetry comics then call them poetic comics.

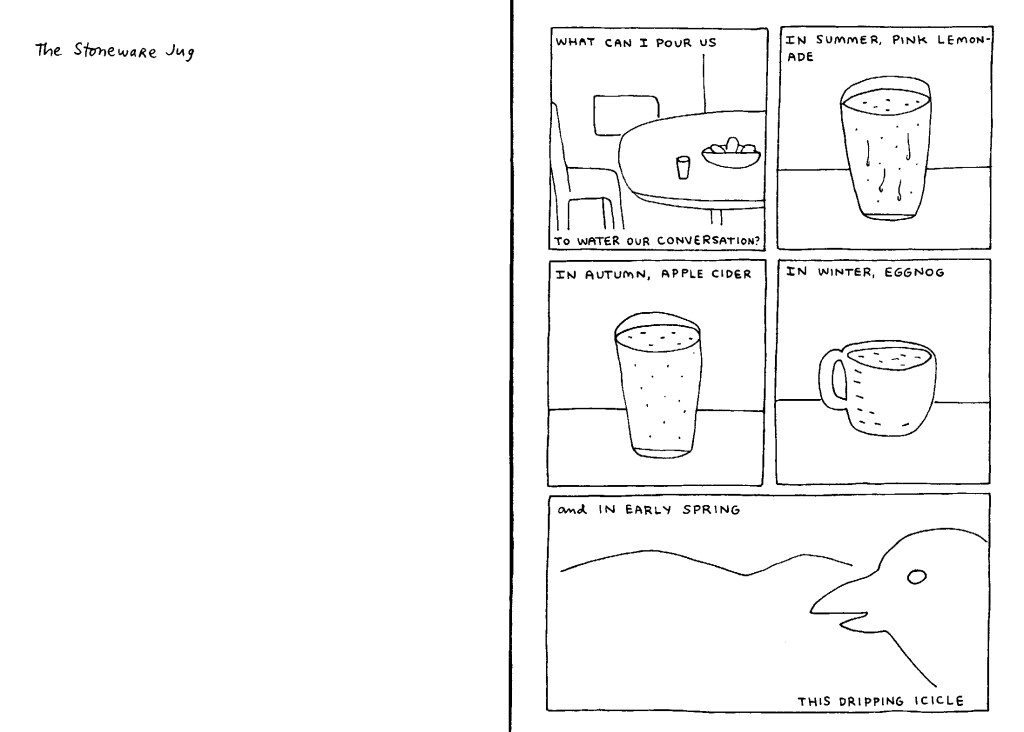

Puddles by Tomas Cisternas (Bored Wolves, 2024). Translated from the original Spanish, these comics by Tomas Cisternas perfectly illuminate his often spare text that focuses on nature, solitude and solace, and being human in the natural world. The work is black-and-white with a simplicity of line that matches the sentiment of the work (totally my sensibility). If you don’t want to call them poetry comics then call them poetic comics.

Along with diary comics of walks, which are often multi-page, the single page comics are particularly poetic. In one panel he writes: “Throughout my life I have wasted time magnificently.” Indeed

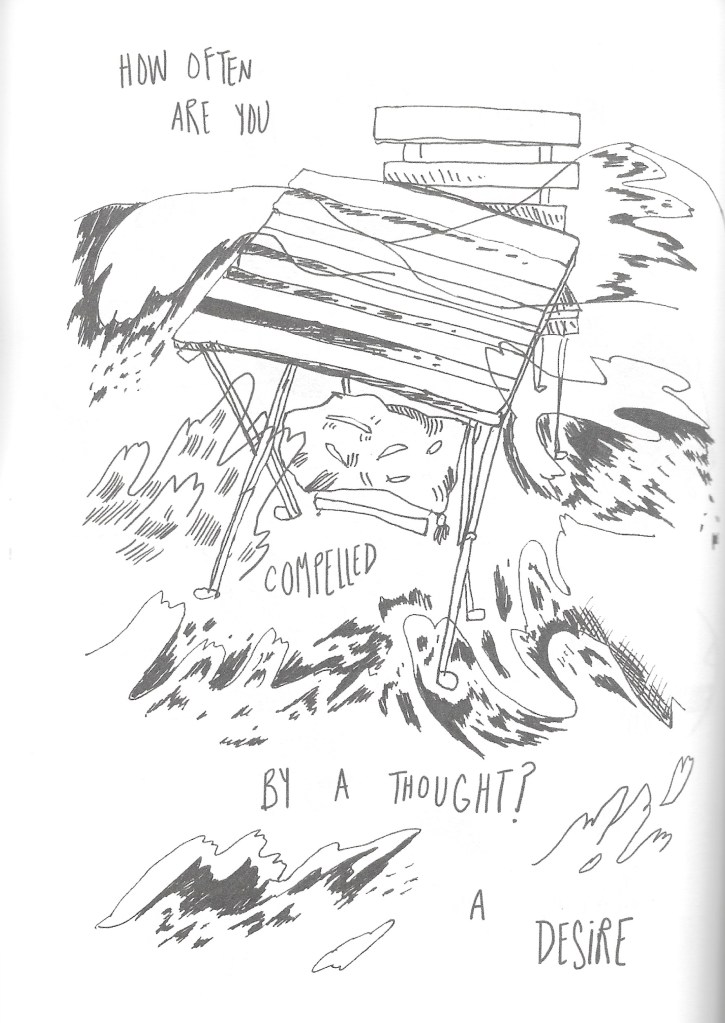

Here’s one of my favorite comics from this collection (it was hard to pick just one) that speaks to the poetry in Cisternas’s work. He adeptly uses the last frame as a “silent” panel (i.e. a picture that doesn’t need words) that puncuates the poem perfectly.

Shout out to Bored Wolves for the translation and making Cisternas work available in English. It’s a beautiful production. Check out the other works the Krakow-based press offers, many of which combine words and pictures.

Metamorphic Door by Carolyn Supinka (Buckman Publishing, 2024) Wild poetry comics are sandwiched between equally wild poems (some illuminated) in Metamorphic Door by Portland poet-artist Carolyn Supinka. In one poetry comic, she writes: “The question / of / who am I / if I’m not / constantly / creating / something.” It’s a question she keeps answering throughout the collection with both words and pictures.

Metamorphic Door by Carolyn Supinka (Buckman Publishing, 2024) Wild poetry comics are sandwiched between equally wild poems (some illuminated) in Metamorphic Door by Portland poet-artist Carolyn Supinka. In one poetry comic, she writes: “The question / of / who am I / if I’m not / constantly / creating / something.” It’s a question she keeps answering throughout the collection with both words and pictures.

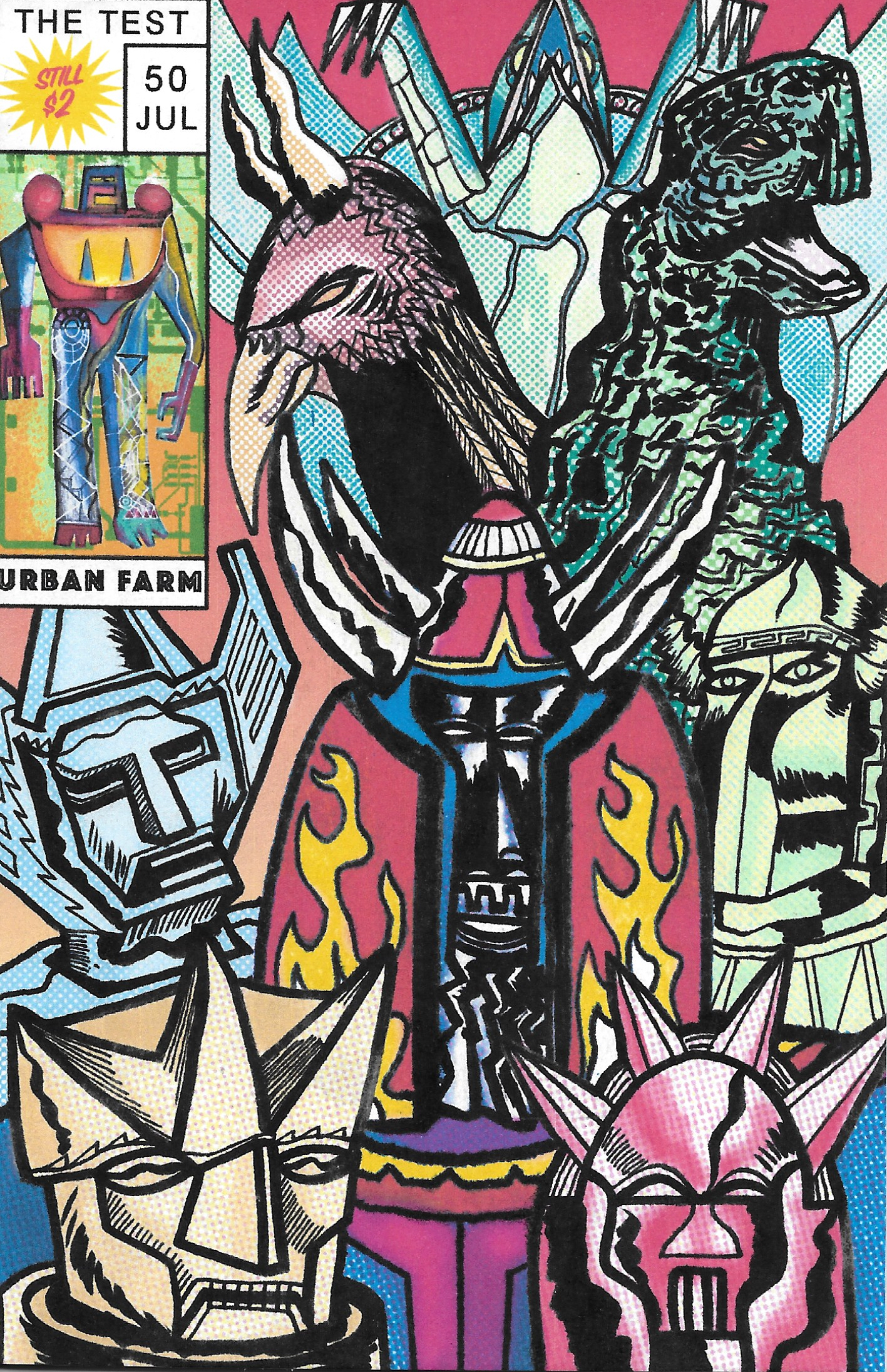

The six poetry comics included here span from two to 10 pages of one-panel or two-panels each. Each panel is multi-layered, drawings of objects that morph intertwined and interrelated, and can disappear totally at times. The text too can’t be contained by the panel. Instead it hovers above, intertwines, and fills empty spaces as it spills down the page. (See AHOPC #12 to compare how bpNichol exploded the frame of the panel in his poetry comics.)

Here’s a representative page from Supinka’s “Earth Tide” that illustrates her style:

Her poetry is more experimental than it may first appear, which perfectly matches her illustrations/illuminations. There are poems that ignore the gutter and spill across the spread; and poems that are literary photo-negatives of each other. The Index is a work of art as well!

BTW I came across Supinka’s collection while browsing the poetry stacks at Powell’s City of Books on Burnside in downtown Portland. Browsing at Powell’s is one of my favorite things to do!

THE TEST #50: In Prasie of Shogun Warriors by Blaise Moritz (Urban Farm Print and Sound, 2023)

THE TEST #50: In Prasie of Shogun Warriors by Blaise Moritz (Urban Farm Print and Sound, 2023)

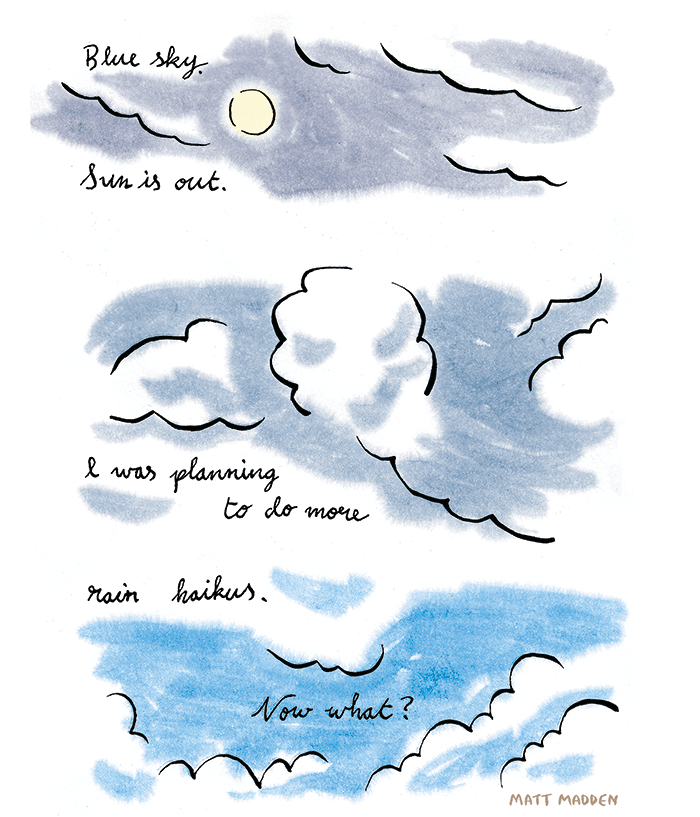

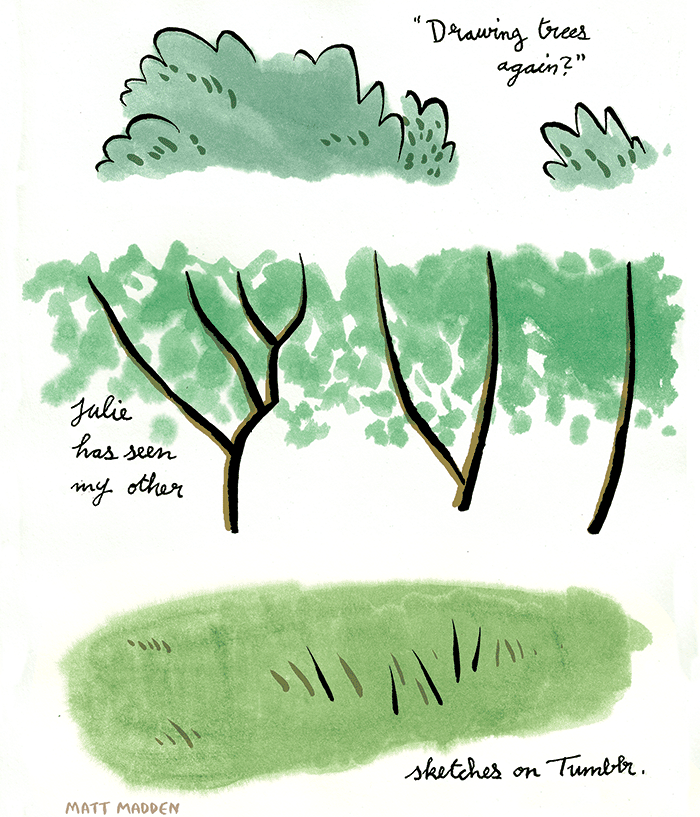

East Toronto artist Blaise Moritz creates poetry comics that are engaging, explosive, and original. He has published two books of poetry (without pictures) in addition to his monthly comic book, THE TEST, and graphic novels, including his latest Bar Delicious (Conundrum Press, 2023). Call Moritz a poet-artist or an artist-poet — either way he smartly uses words and pictures to illuminate and expand context.

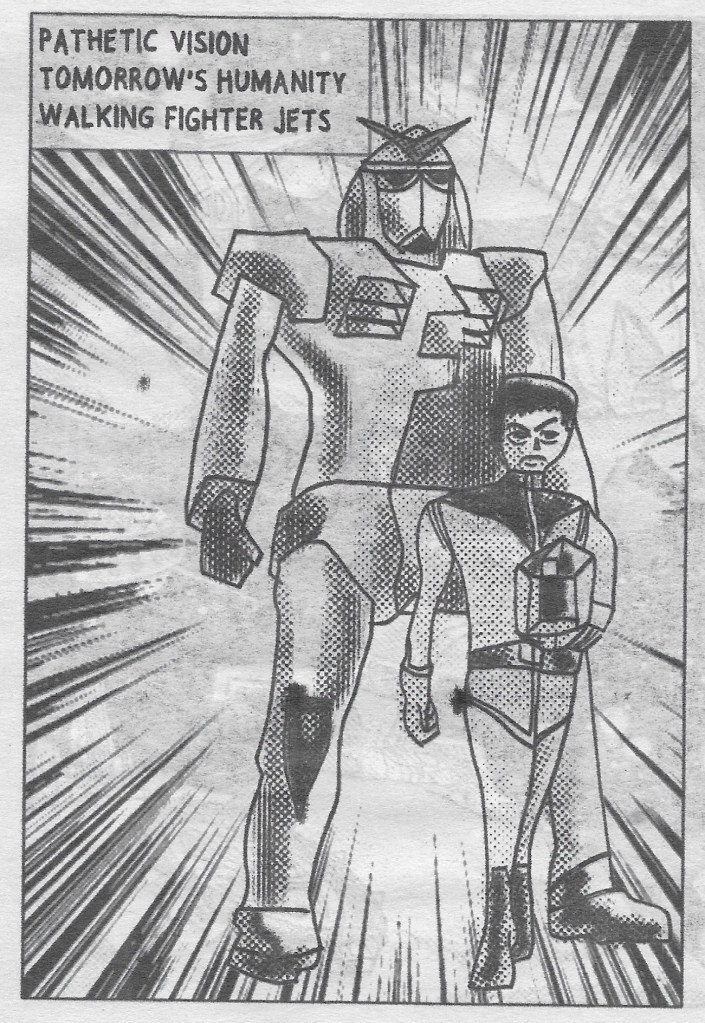

His piece “In Praise of Shogun Warriors” in THE TEST #50 (Urban Farm Print and Sound, 2023) features linked haiku stanzas (from 2015) that Moritz illustrated in 2023 with Gundam-inspired robots remembered from his childhood (including Shogun Warriors fan art he made when he was 8 or 9 years old). Japanese haiku (three lines of 5-7-5 syllables) aptly fit this subject matter; it’s perfectly played. Here’s a sample from the 16-page poetry comic:

Other examples of his poetry comics can be found online by following Moritz on Instagram. Some of his single-panel poetry comics are reminiscent of Kenneth Patchen’s picture poems. He also makes music as The New Birds of America (underscoring the poet-artist drive to build additional context for when we’re asked, “What does it mean?”)

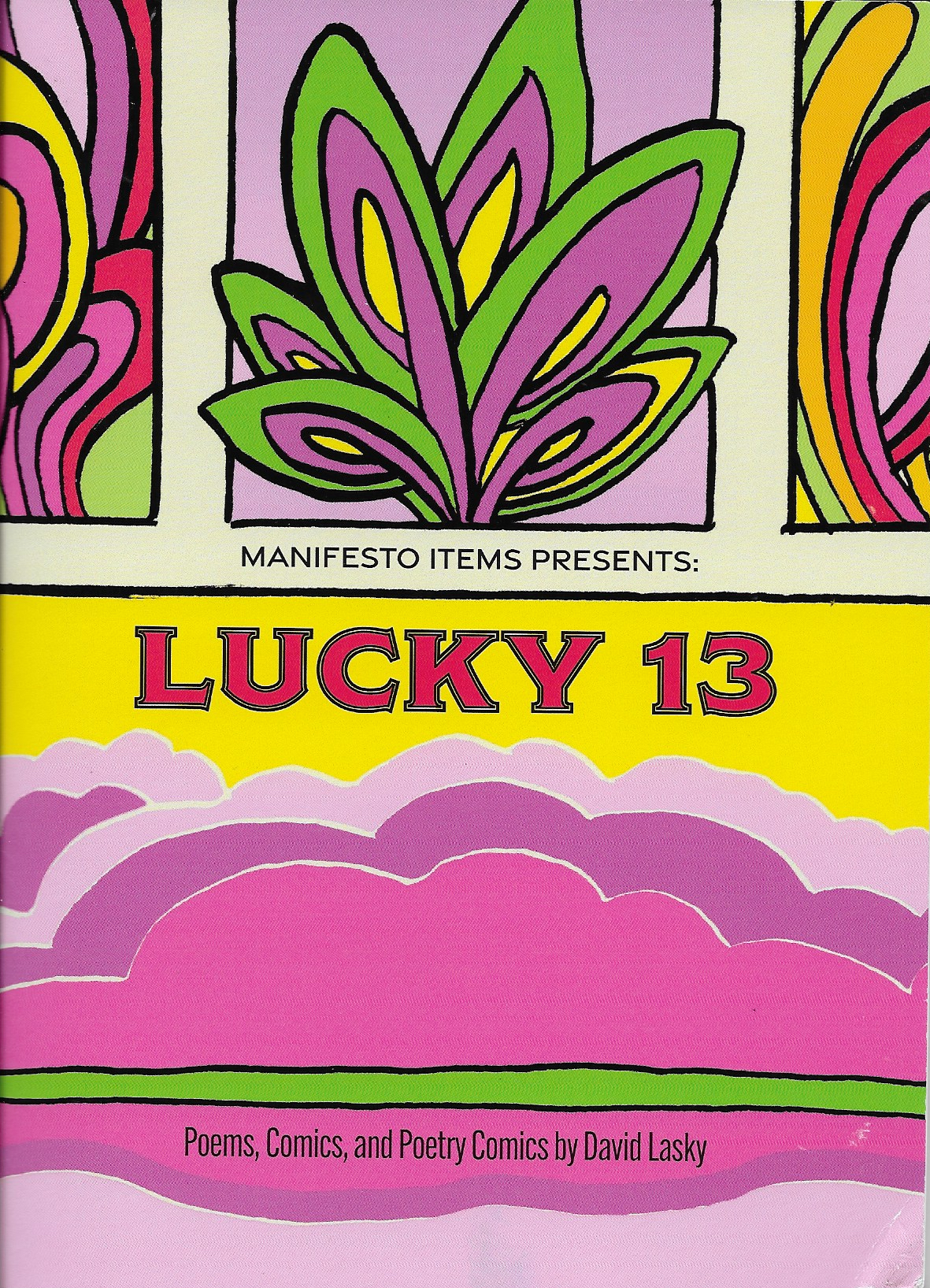

Thanks to David Lasky for recommending Blaise and sharing his THE TEST comics with me.

Timeline: Current

Warning: This incomplete history maps my journey as a poet learning about comics and doesn’t follow a strict chronological order.