A History of Poetry Comics #34

Variations in Panel Layouts for Haiku Comics

Haiku is one of the shortest poetry forms. Haiku Society of America defines haiku as “a short poem that uses imagistic language to convey the essence of an experience…” Originating in Japan, classic haiku (1600s-1900s) almost always followed a 5-7-5 syllabry count; often included a kireji (cutting word) that emphasized or set up the haiku’s “a-ha moment;” and used a kigo (season word) to indicate the time of year. The classic syllabry count of 5-7-5 translated into English-language haiku as three lines with a syllable count of 5-7-5. And that’s how many of us learned to write haiku.

Haiku comics creators have brought unique approaches to addressing the restraints of the form. While it seems natural to spread the haiku over three panels, aligning with the traditional syllabry count, there are one-panel, four-panel, and multiple-panel examples that show the creativity of the poet-artist and the elasticity of haiku.

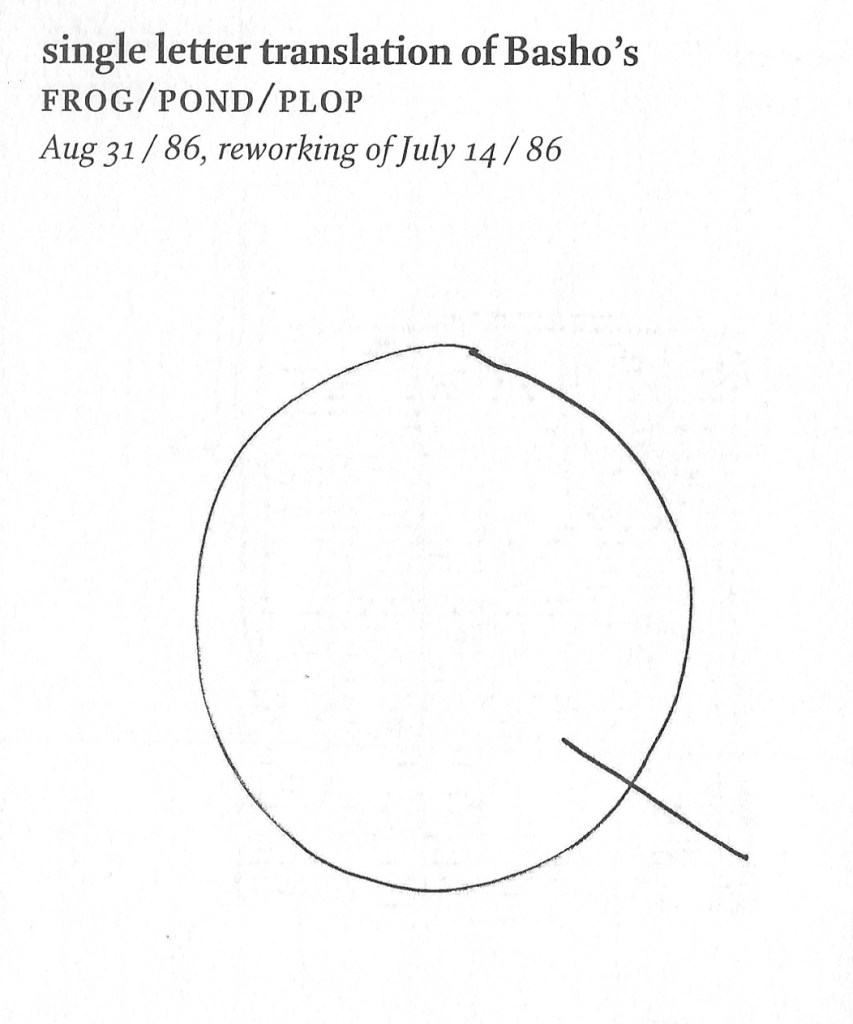

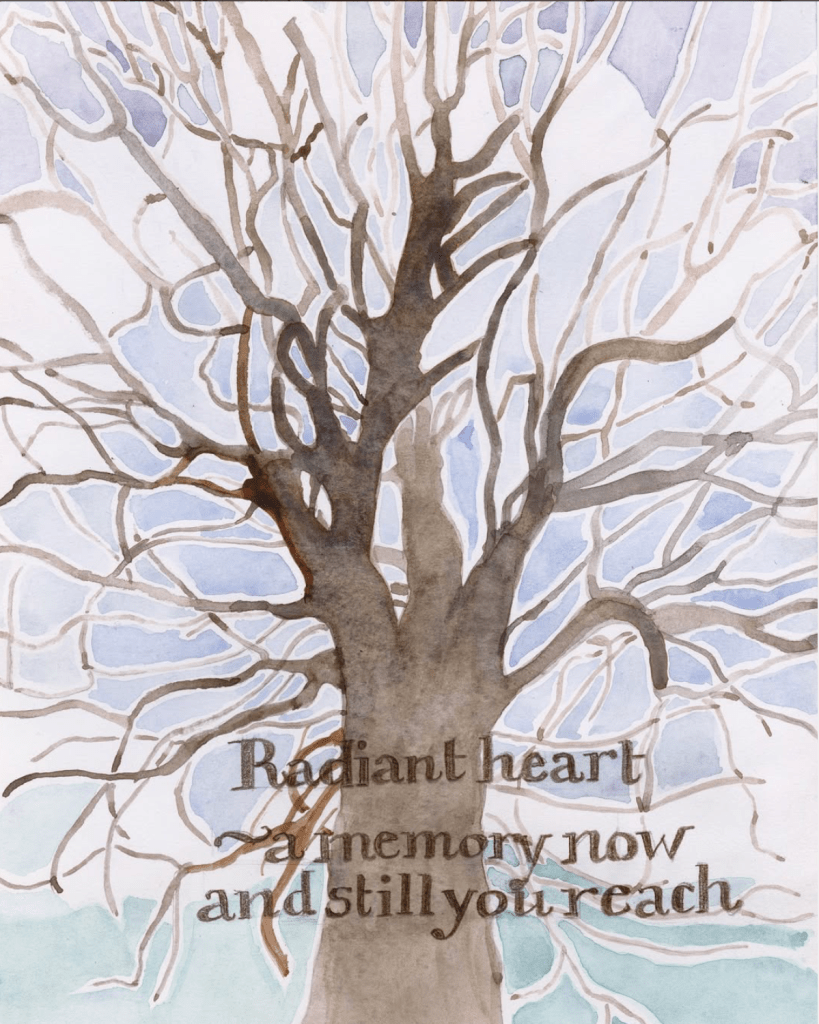

One-Panel

One-panel haiku comics often evoke haiga, the Japanese art form that combines haiku with a picture. The best examples are ones where the picture complement the poem or adds a second (or even third) meaning. (See AHOPC #03 for a classic example of haiga.) Artist Monica Plant, who creates Haiku Comics of the Hamilton Bay, has great examples of haiku comics, including one-panel ones that evoke haiga.

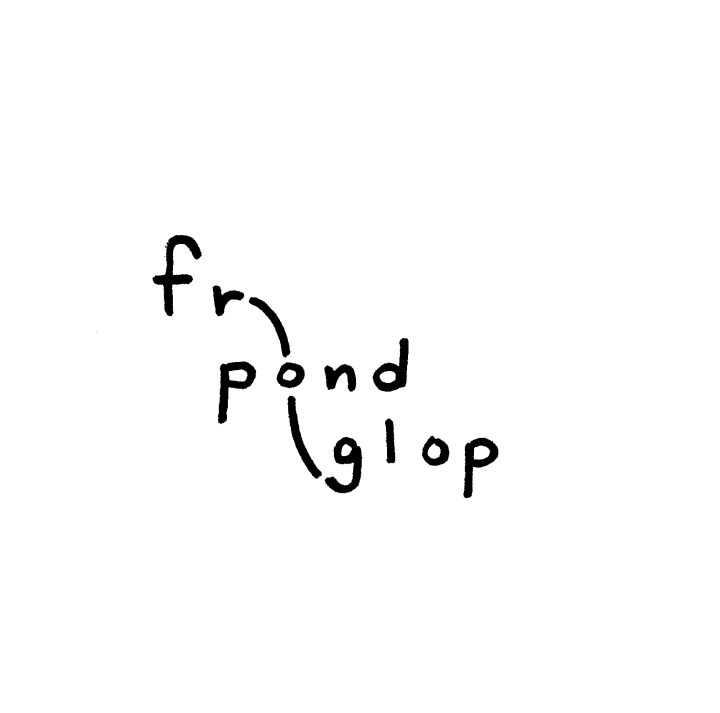

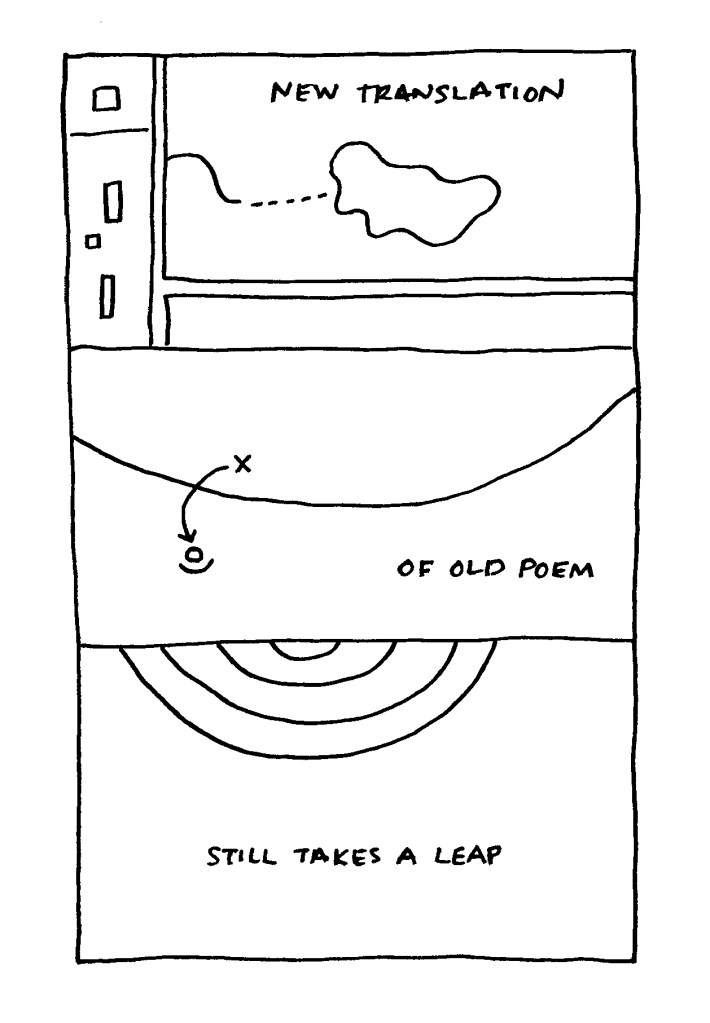

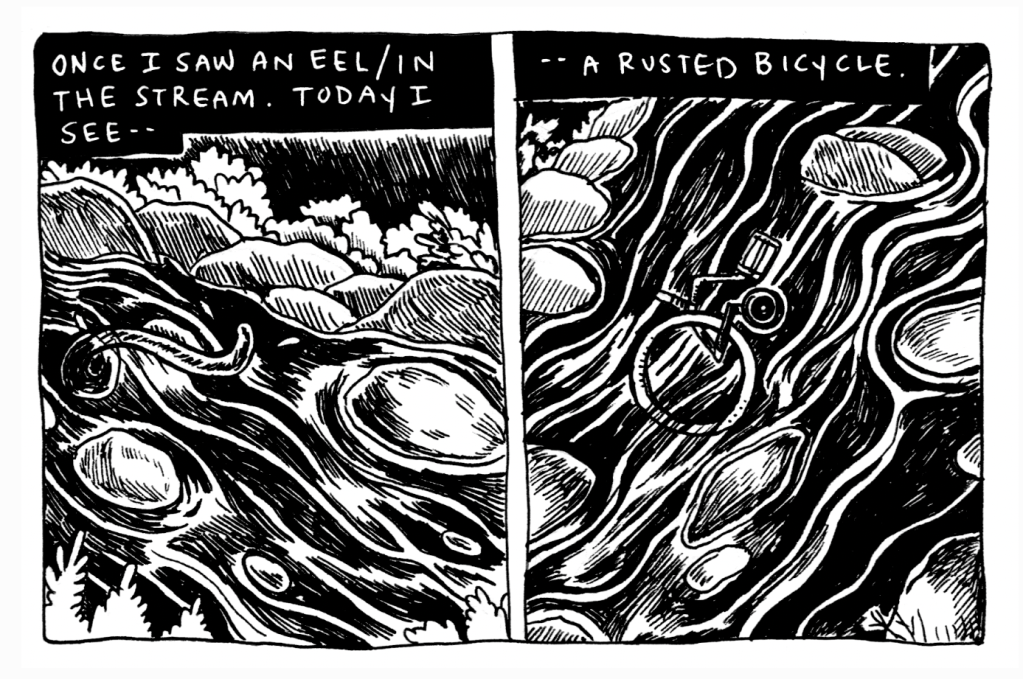

Two-Panel

Two-panel haiku comics are perhaps the most challenging–at least at first glance. Most classic haiku are in two parts (despite the three-line trope) and almost always cut after the first or second “line.” (Yes, there are haiku that cut in the middle of the second line too.) In two-panel haiku comics then, the “cut” is between the one panel transition. Summer Pierre has great examples of this approach and notes on her blog, “Its one- to two-panel format makes it a brief and doable way to record something in my day.”

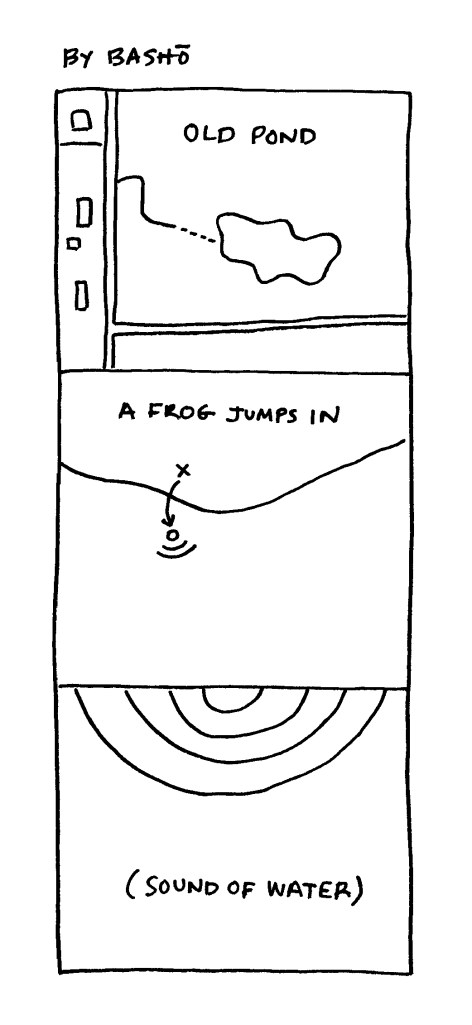

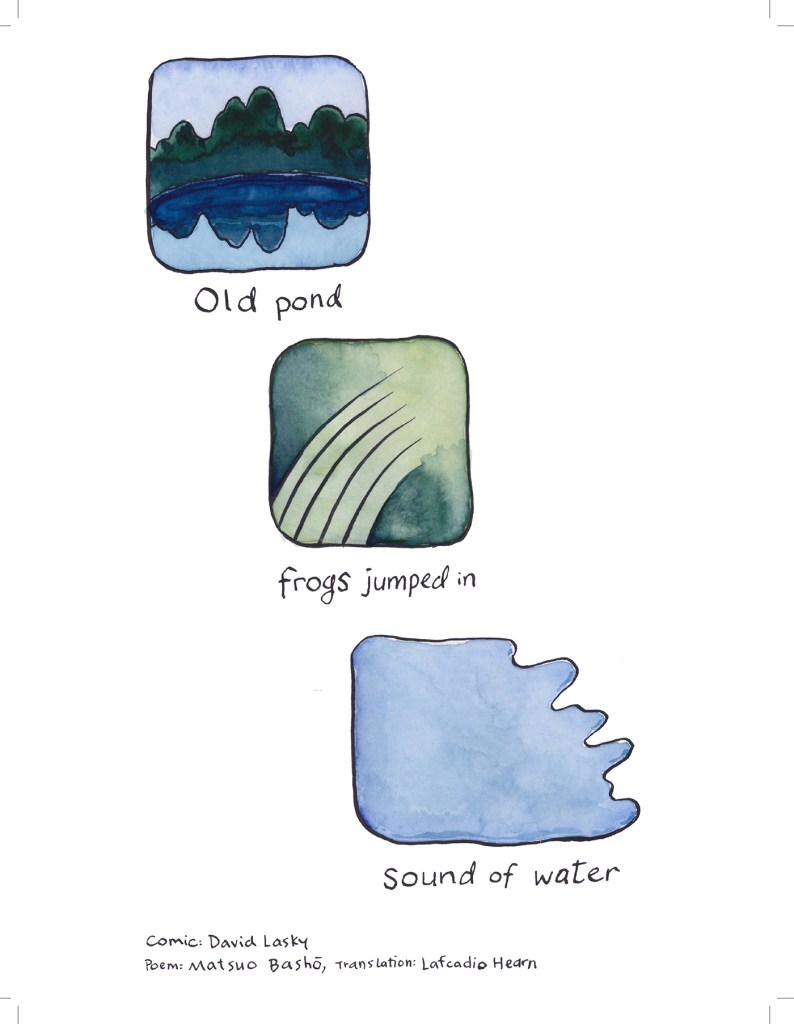

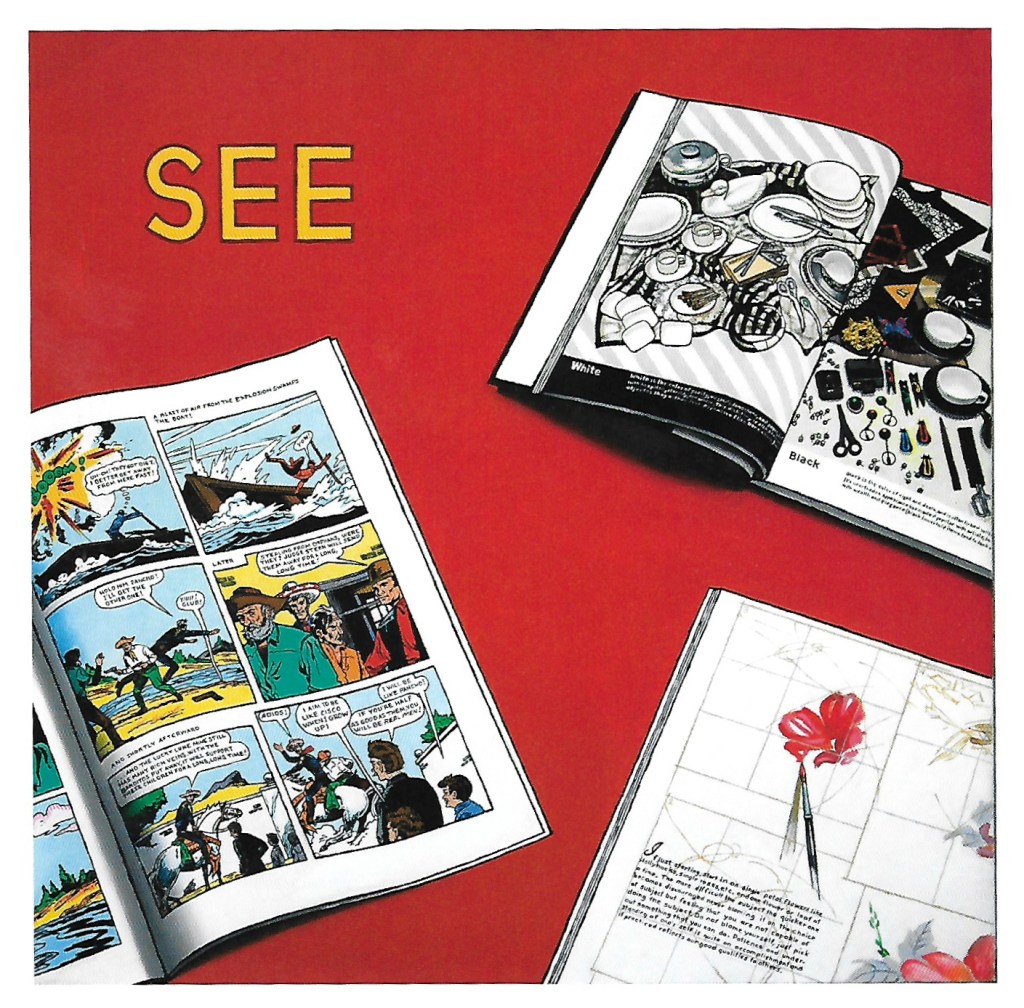

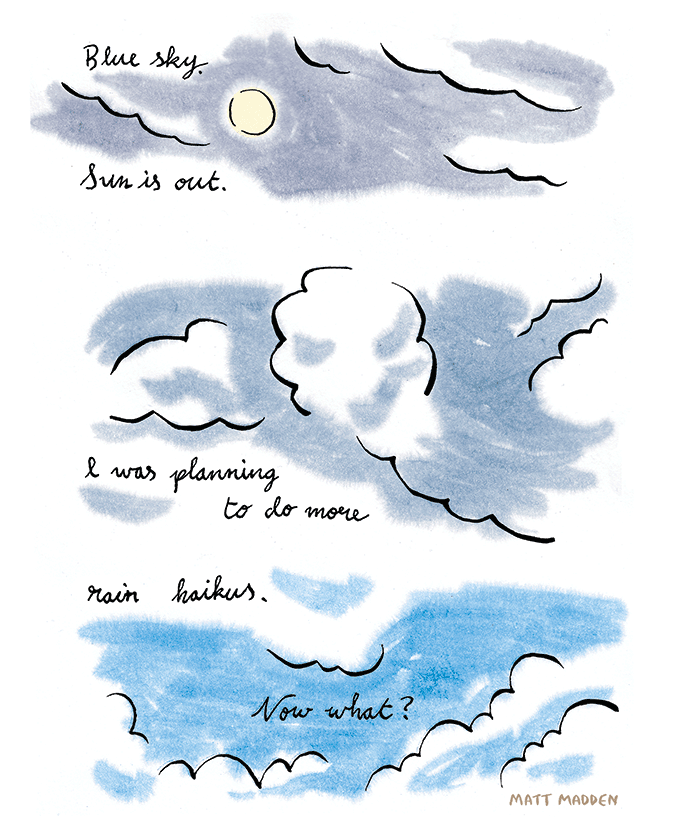

Three-Panel

Three-panel haiku comics may seem the most obvious since the panel count matches the line count of a classic haiku. Not surprisingly though, comics artists have brought various approaches to this format. David Lasky (full disclosure: he’s my comics teacher) evokes the feel of a comic strip, while Matt Madden implies three stacked panels that coalesce into a whole.

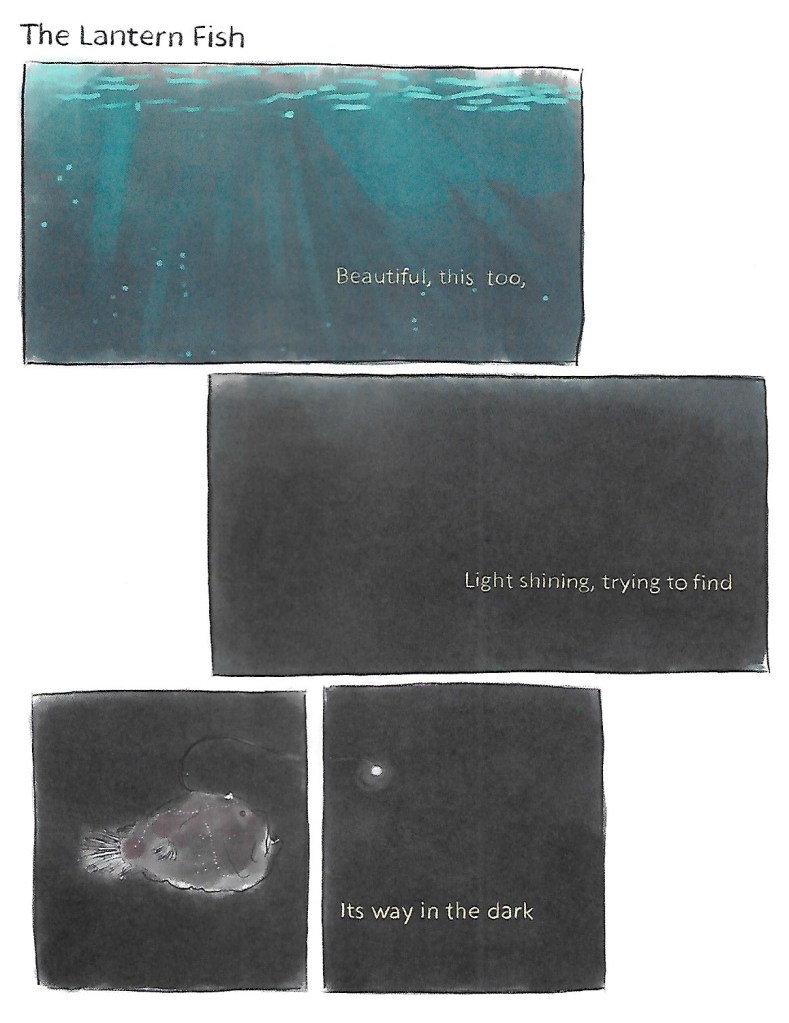

Four-Panel

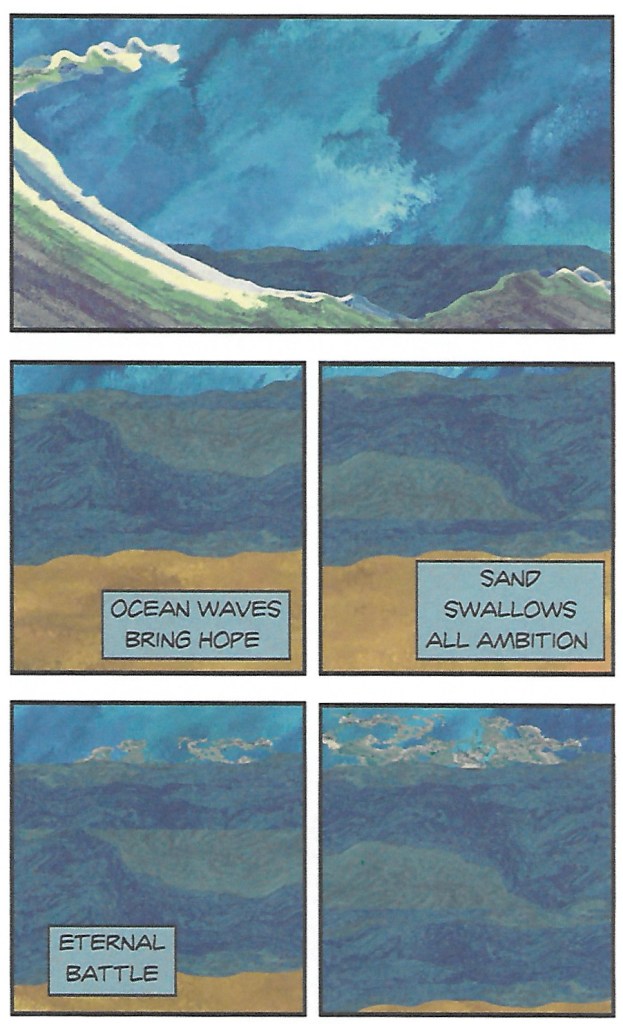

For good reason, four-panel comics are a great match for haiku. Four panels give the comics artist the chance to create a pause in the haiku that mimics the kireji, the cutting word. It can also bring in additional information, visually complete a thought, and/or extend the meaning. In this example by Susanne Reece, she uses the panel without a line of the haiku to set up the final reveal.

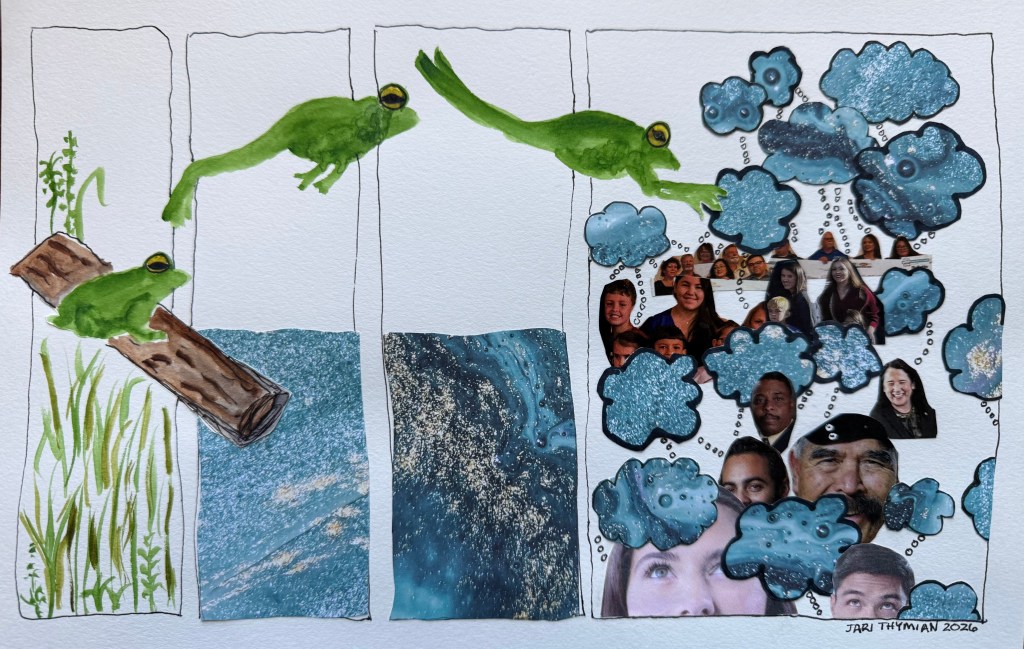

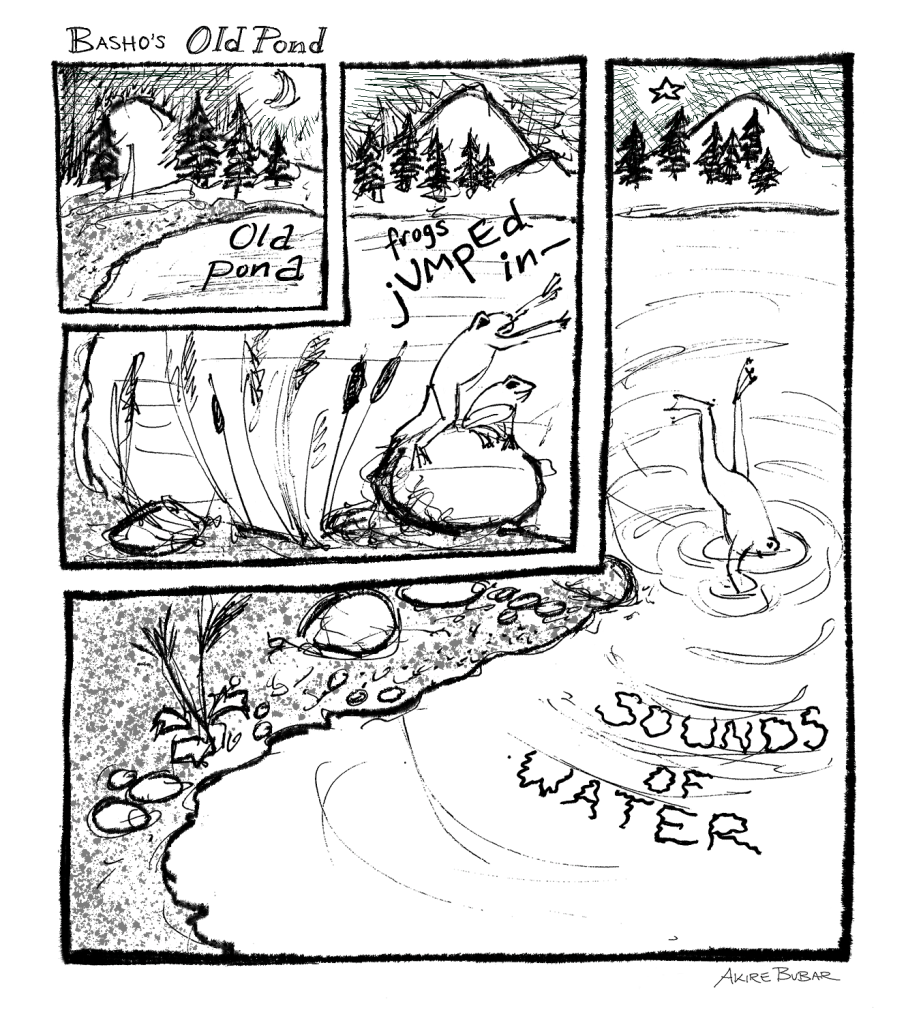

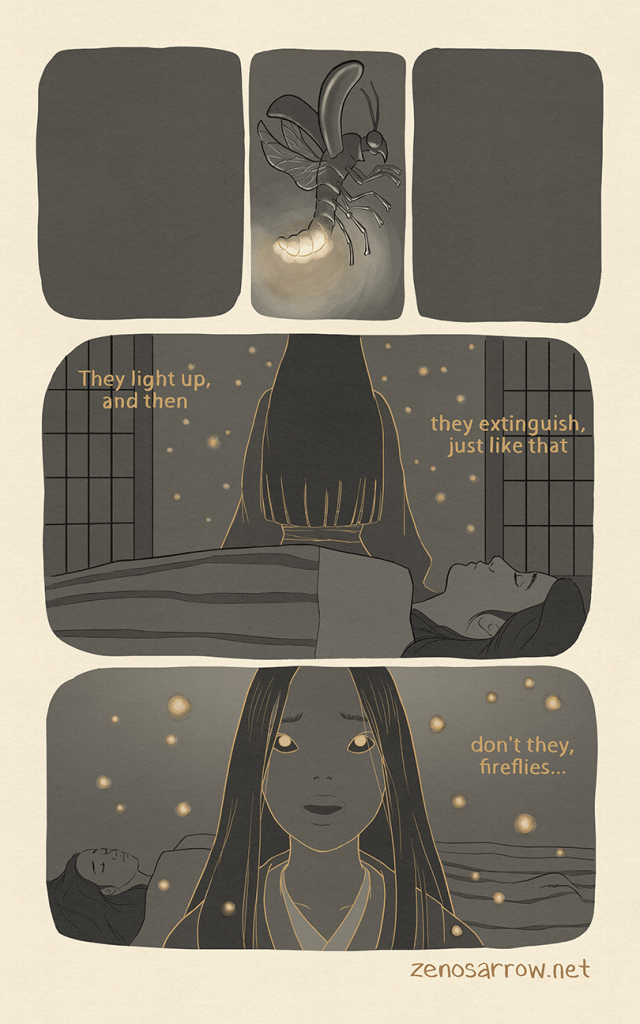

Multiple-Panel

Using more than four panels give the comics artist room to add context, set the scene or season, and/or indicate a cut or leap in the haiku. They often have the feel of a graphic novel. Conjuring the look and feel of a page from a comic book, Jason McBride uses multiple panels to expand his haiku.

It’s fun to think that a short poetry form such as haiku can be the catalyst for so much variation! Haiku comics creators are continuing the long history of pictures and words working together to add context, deepen meaning, and capture moments in ways that words or pictures can’t always do by themselves.

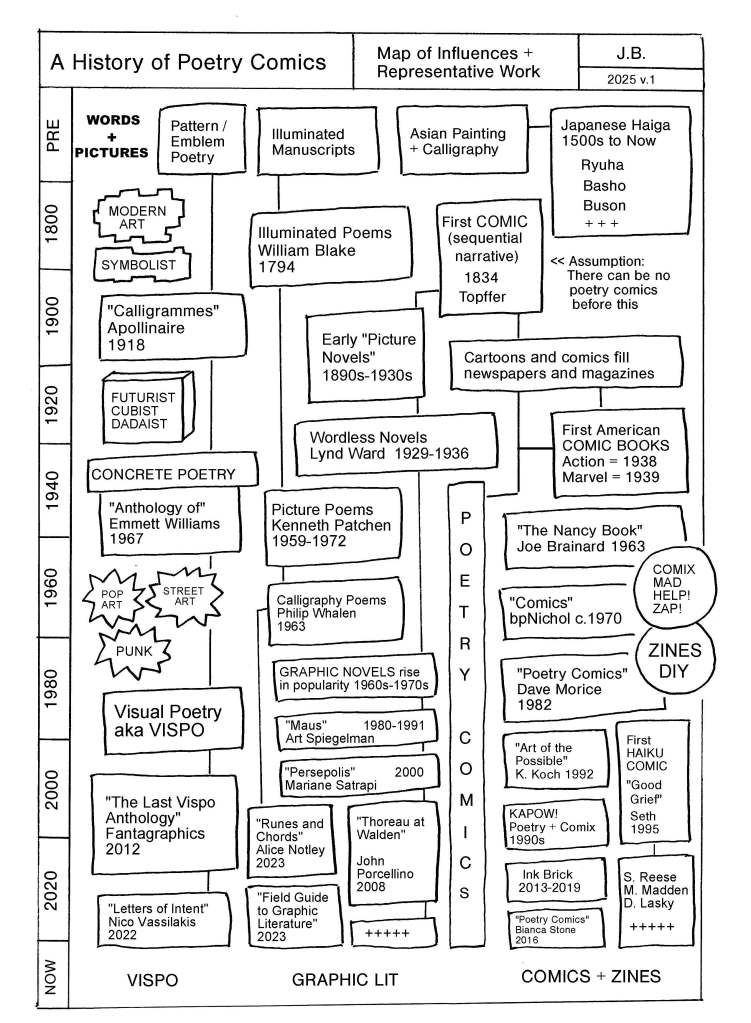

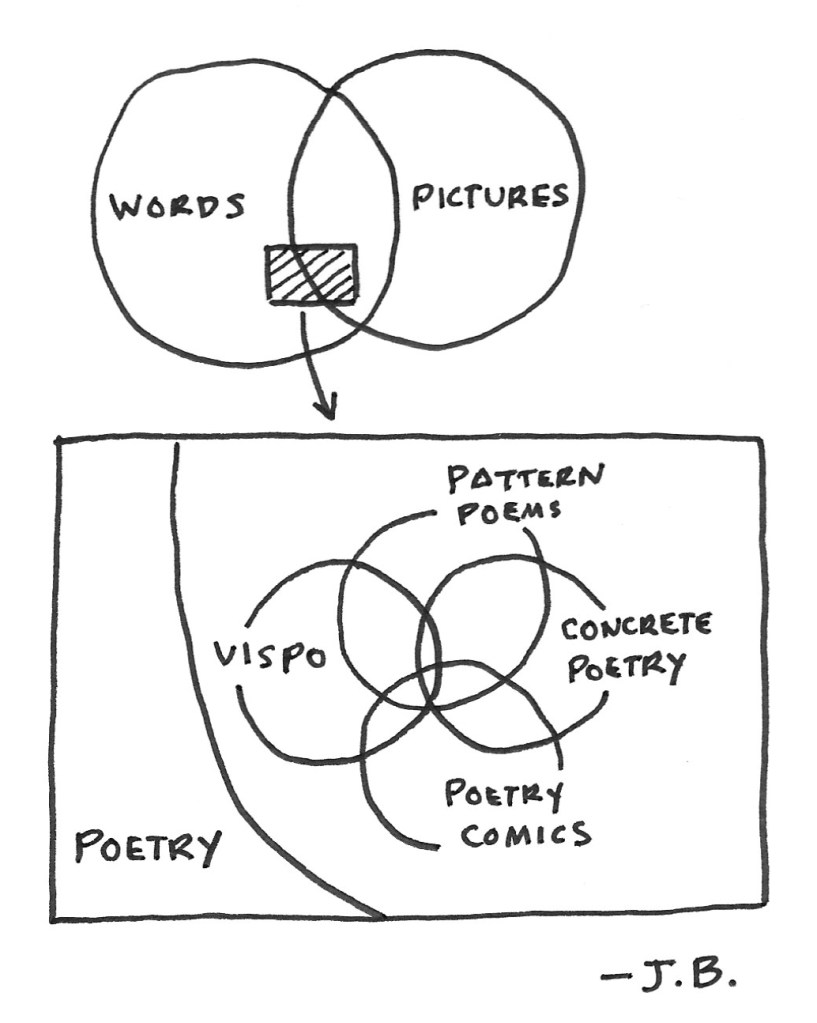

Timeline: Current

Warning: This incomplete history maps my journey as a poet learning about comics and doesn’t follow a strict chronological order.