More Book Reviews

The more I look, the more I find! Here are some books of poetry comics worth checking out. (They’re in descending order of publishing date.)

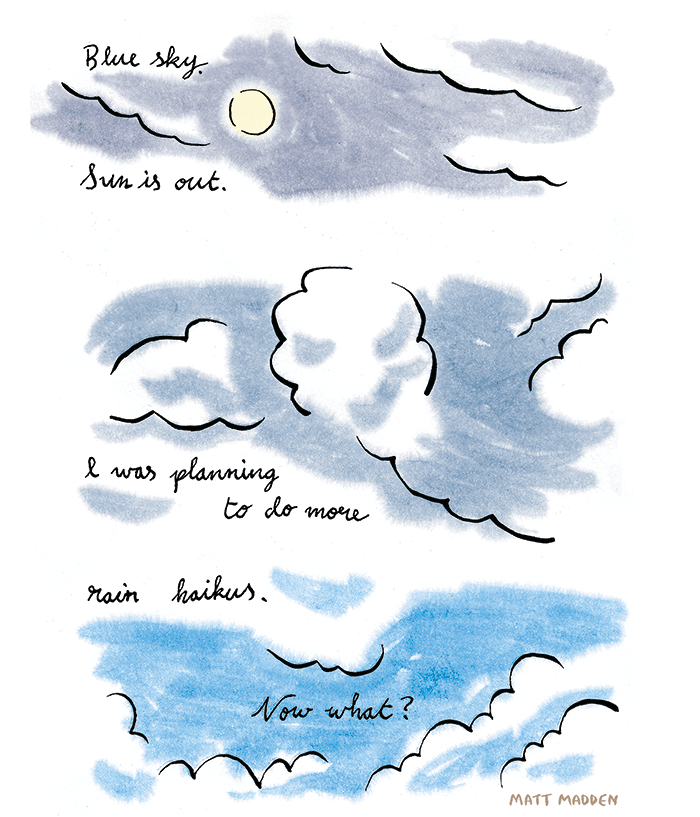

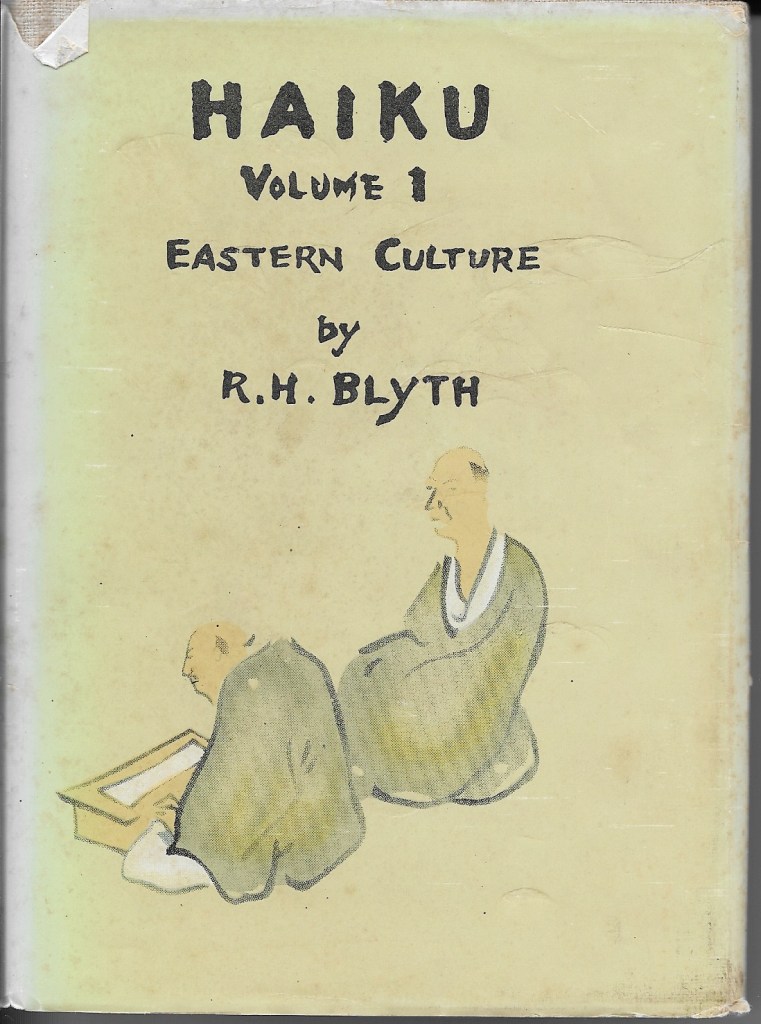

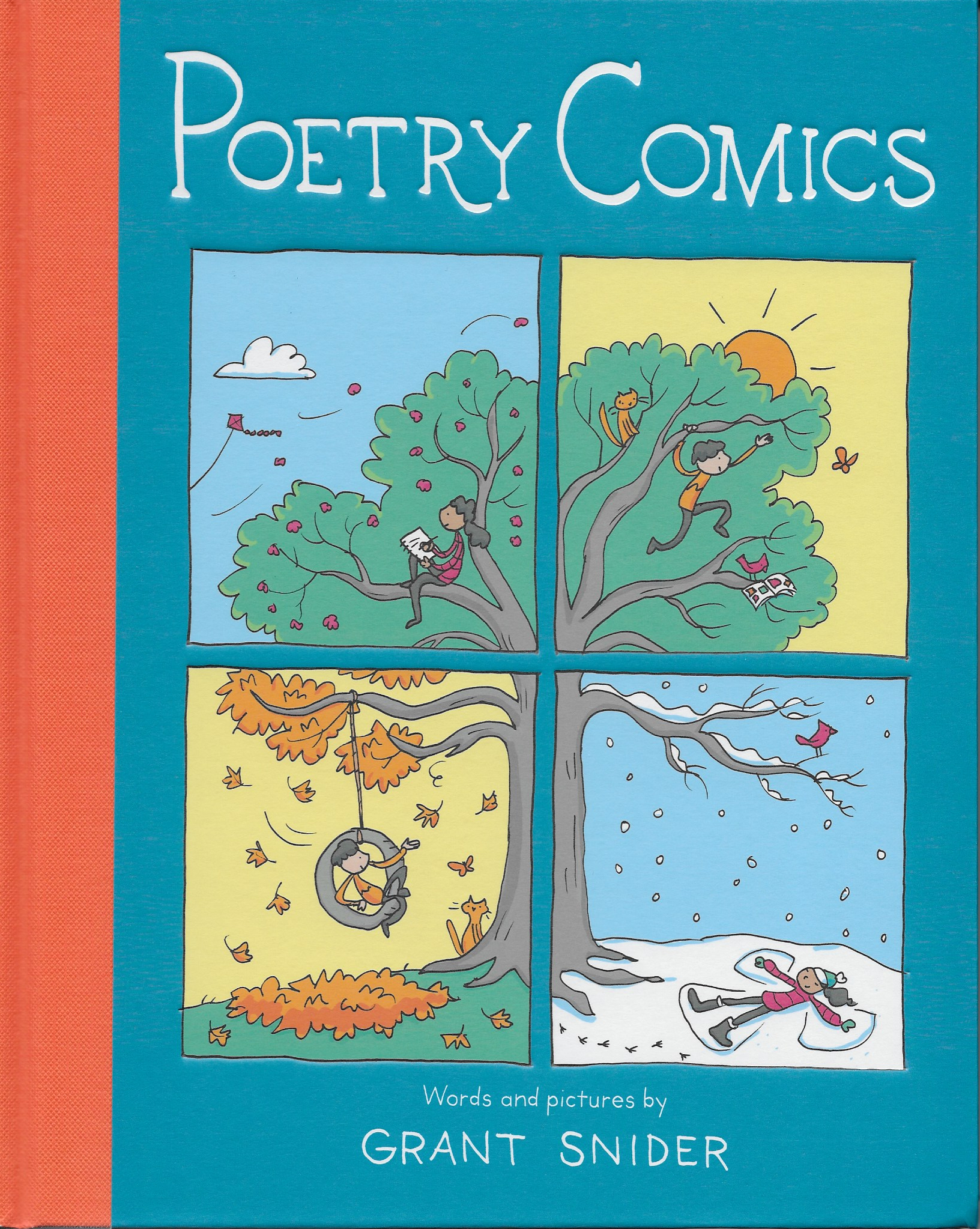

Poetry Comics by Grant Snider (Chronicle Books, 2024). Fun introduction to poetry comics for a YA audience, Grant’s colorful comics provide both inspiration (e.g., “Becoming” and “A Moment”) and instruction (e.g., “How to Write a Poem” series) for budding poets and their teachers. Organized by season, the shorter poems especially feel like haiku, and in fact there are haiku comics included. More of his work can be seen on Instagram @grantdraws.

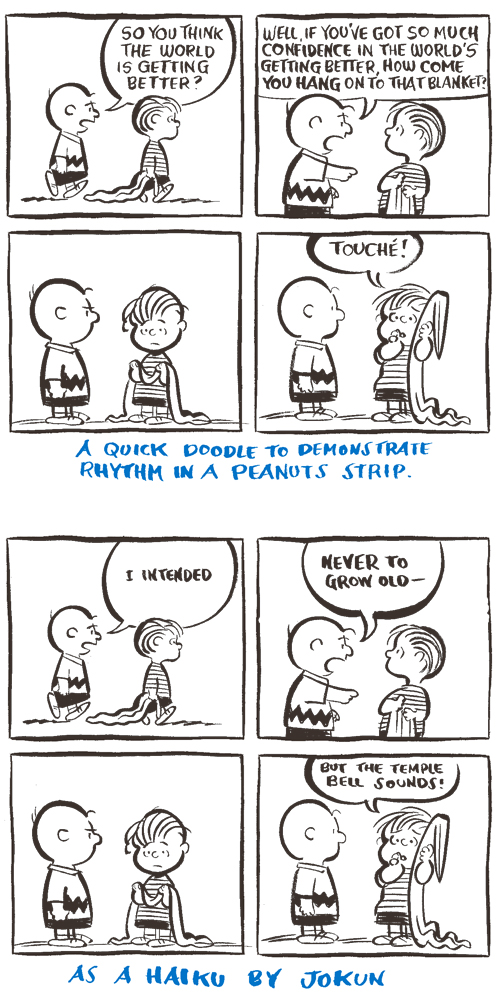

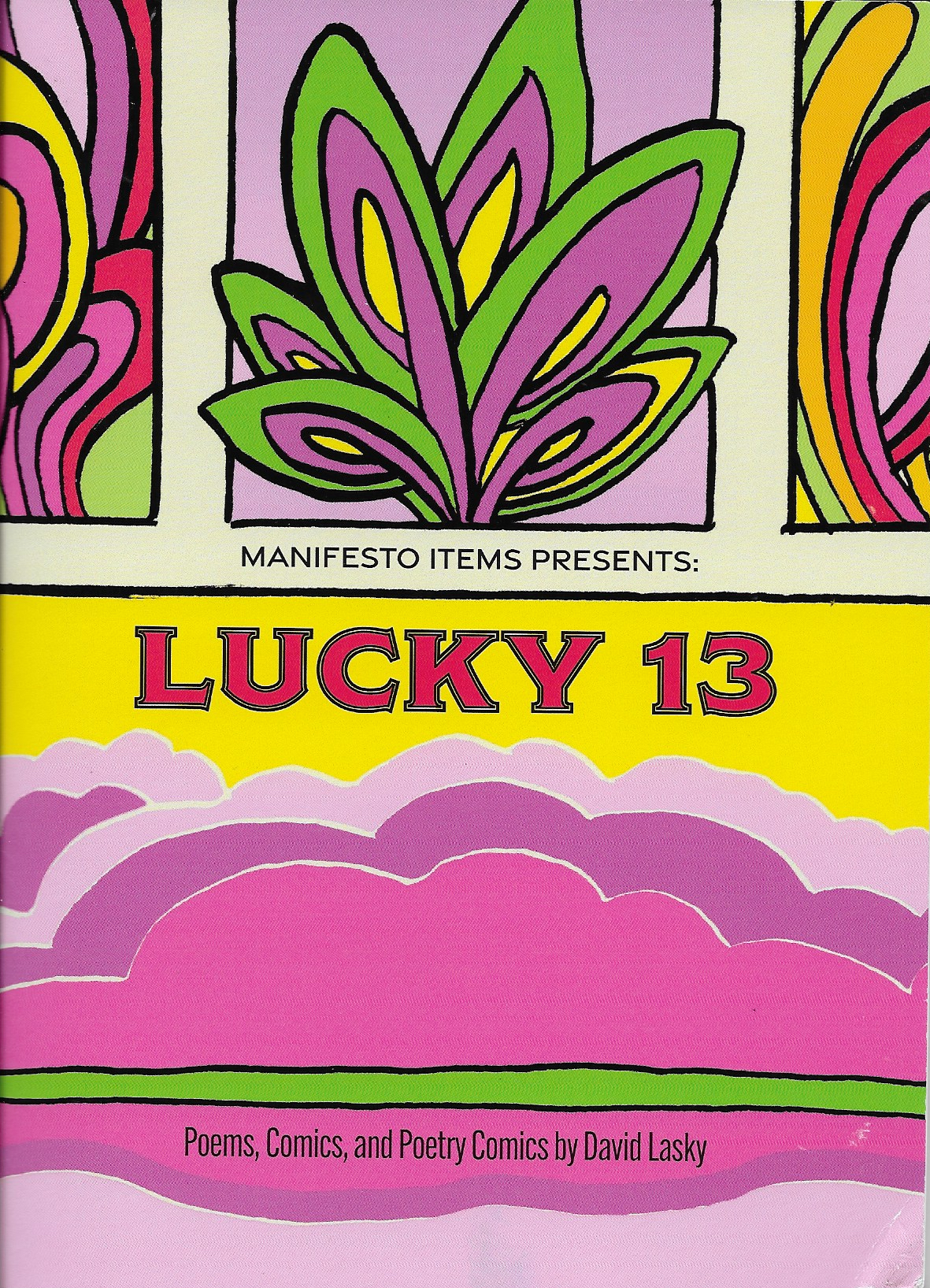

Lucky 13 + Summer Haiku by David Lasky (DIY, 2023). My teacher and friend David Lasky continues to be an inventive creator of poetry comics and haiku comics. As he says in his “Mix Tape” comic in “Lucky 13:” Every good teacher is also a student. Indeed. His 2023 DIY zines are both filled with poetic moments seamlessly integrated into his accompanying art. His collection of 12 haiku comics in “Summer Haiku” shows his increasingly deep (deep in the sincereset sense) understanding of haiku. He’s an artist-poet who’s fast becoming a poet-artist! Check his Etsy site for availability–his zines always go fast!

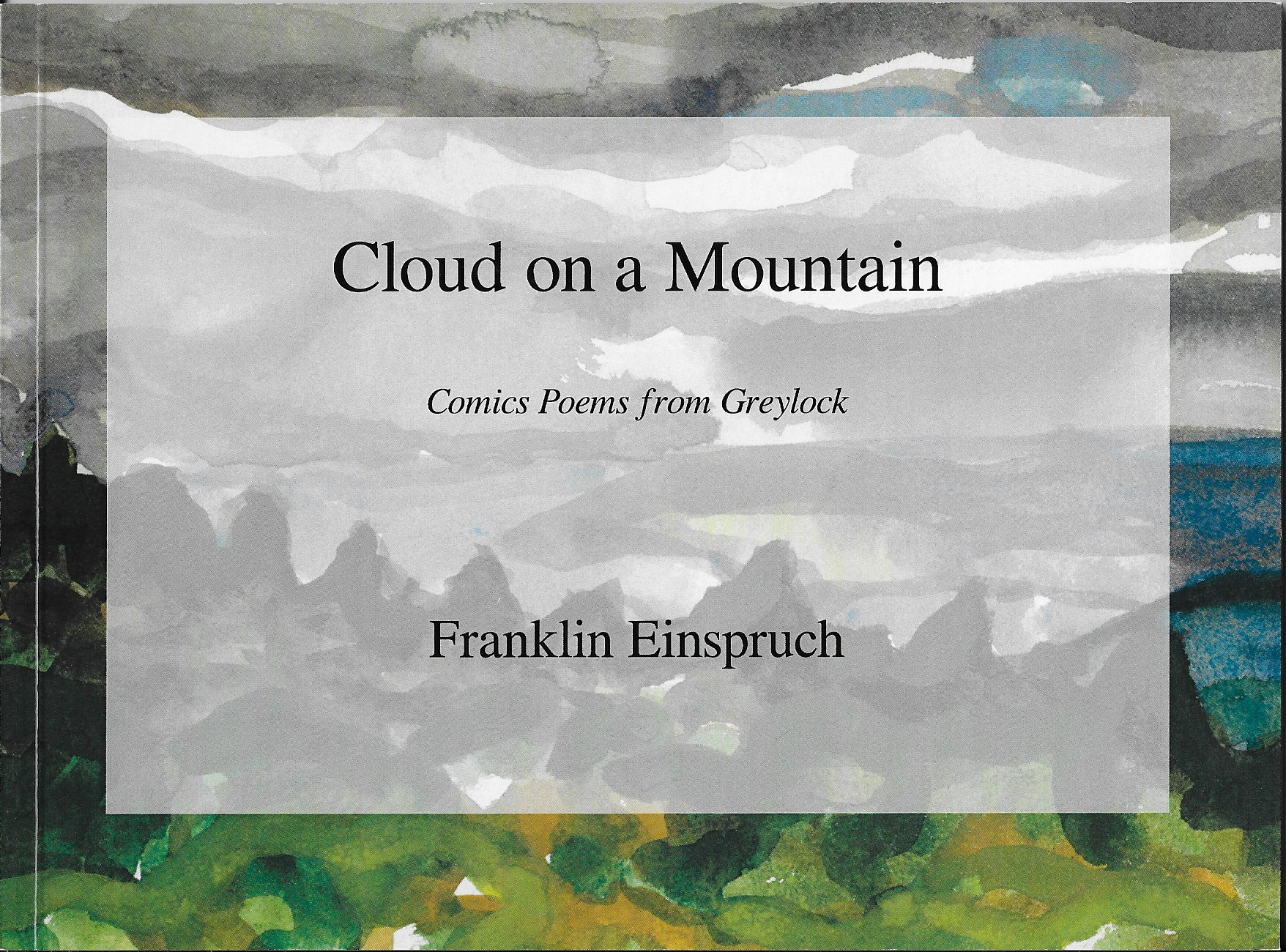

Cloud on a Mountain – Comics Poems from Greylock by Franklin Einspruch (New Modern Press, 2018). Franklin Einspruch has a painterly approach to poetry comics. His art is dense and deeply colored. The haiku-like poems are hand-lettered and often fully incorporated into the artwork. The poems in “Cloud on a Mountain” (currently out of print, with the promise of a second edition) each spill across two panels, creating space and giving time for the meaning to form and land. See his art and poetry at https://franklin.art.

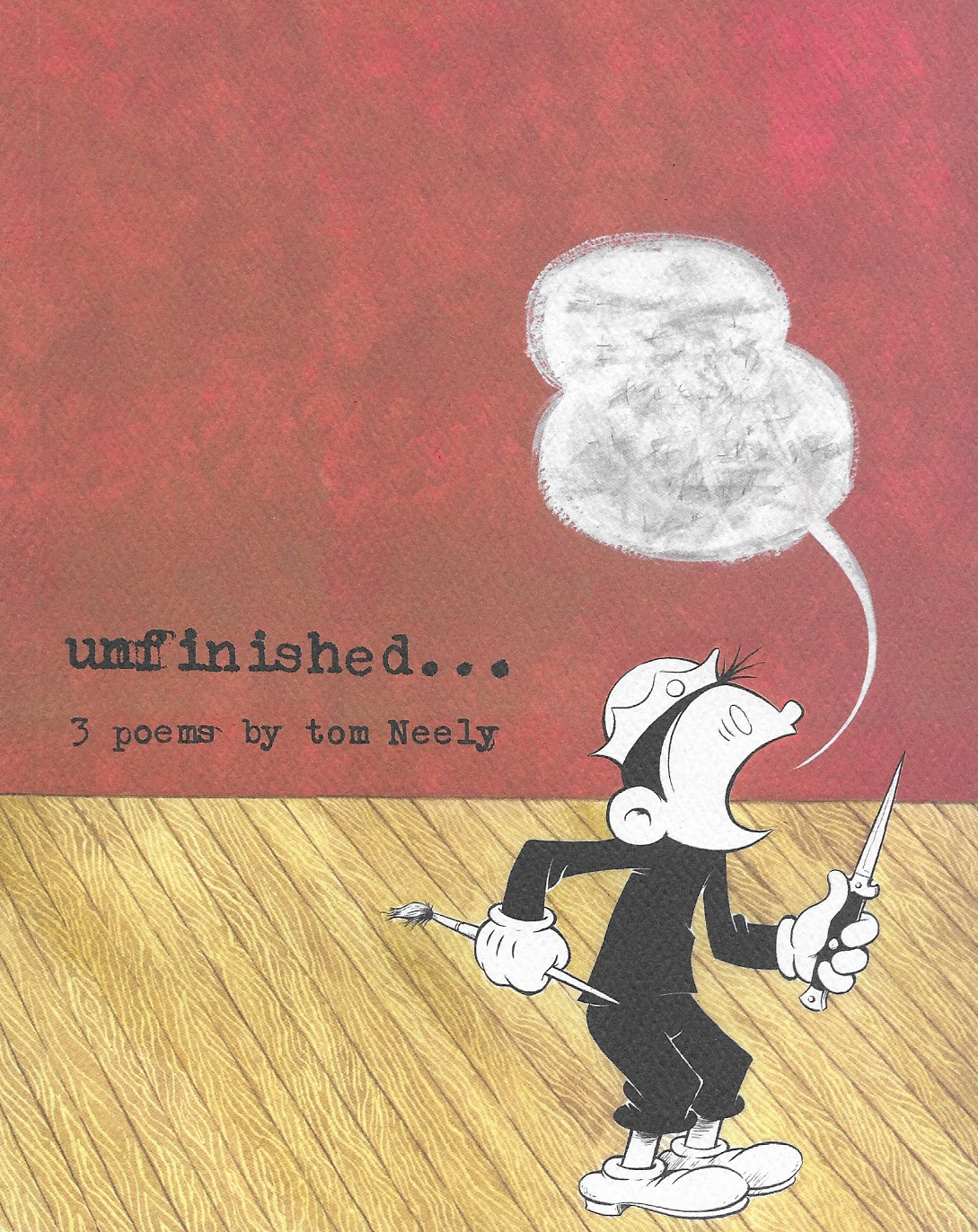

unfinished … 3 poems by Tom Neely (DIY, 2017). Man, these are heart-wrenching poetry comics about the loss of a friend. Tom Neely brings his comic artistry, a very punk, comix-influenced style, to tackle this painful experence — taking three years to complete and another four years before publishing it. Each page is a single panel, with the last poem fading over several pages to an empty panel that becomes a poignant eulogy to “an unfinished life…” See more of Tom’s work on Instagram @iwilldestroytom

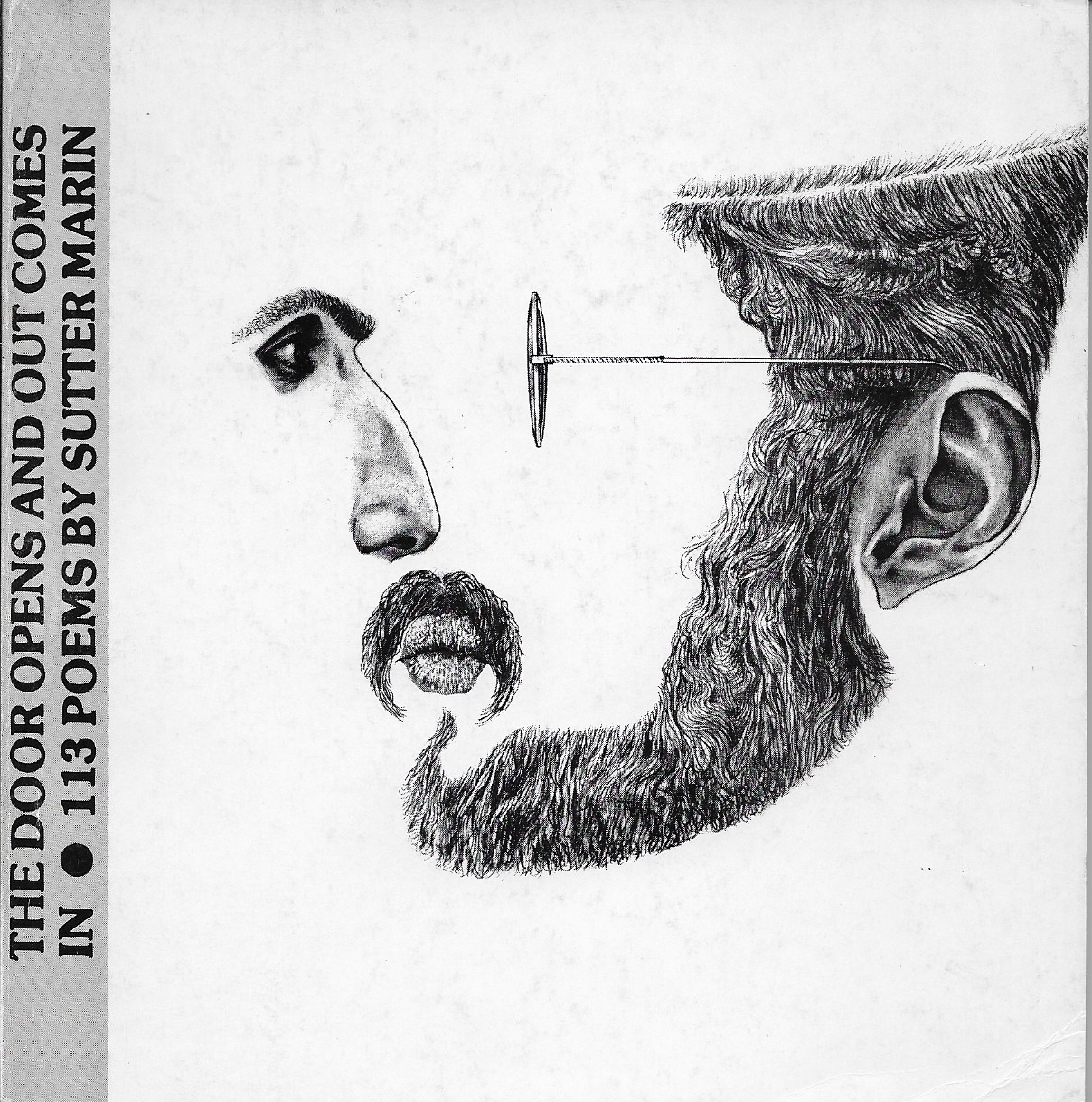

The Door Opens and Out Comes In by Sutter Marin (Underlying Press, 1979). Not sure these qualify as poetry comics, perhaps definitely in kindred spirit with picture poems. Many of the 113 poems by Sutter Marin in this collection are illustrated with diagrams, simple figures – human and otherwise – and/or animated everyday objects. Humor abounds. Sutter was an atist (he died in 1985) associated with the North Beach Beats and notably illuminated poetry by Beat poet ruth weiss.

Happy Poetry Month!

Timeline: 1979-2024 (but new to me!)

Warning: This incomplete history maps my journey as a poet learning about comics and doesn’t follow a strict chronological order.