musings on words + pictures by R.H. Blyth

Here’s some found text that provides additional thoughts on words and pictures from R.H. Blyth in the classic Haiku Vol. 1 Eastern Culture published in 1949.

Although Blyth is discussing painting and poetry in context in terms of Japanese haiga – brush paintings that illuminate a poem, often times a haiku (first discussed in AHOPC #03) – I think it’s relevant to poetry comics. His comments support my belief that drawing and writing together can illuminate and transcend what they can’t always accomplish singularly. (See also “What are poetry comics” in AHOPC #05.)

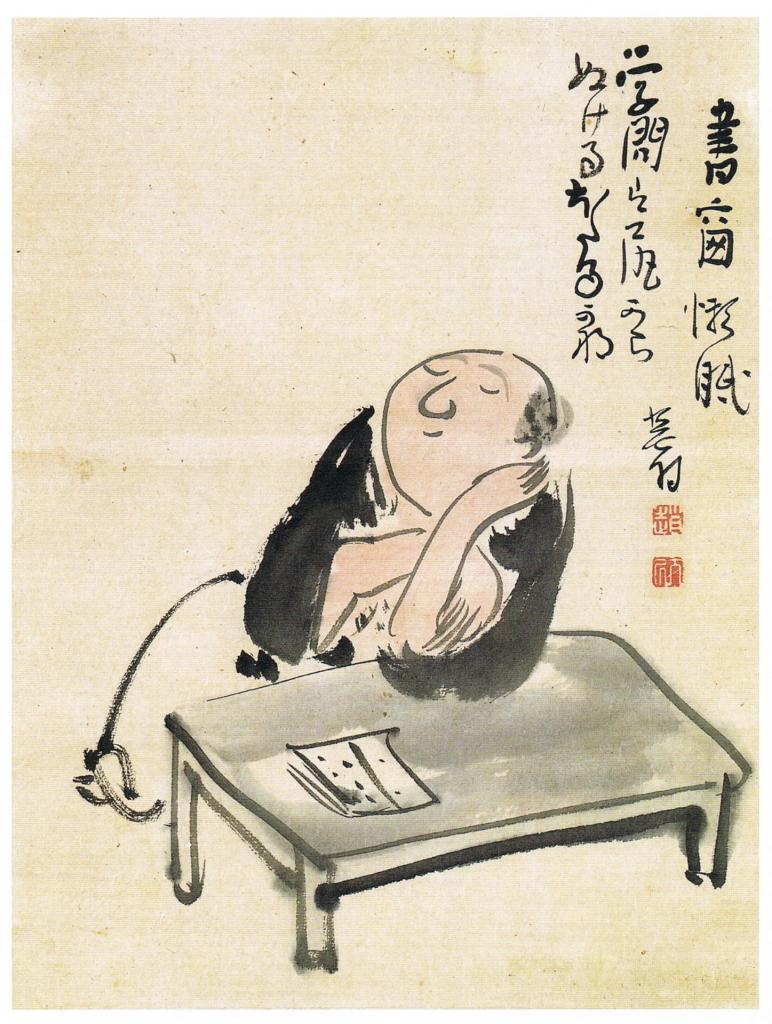

The qualities of haiga are rather vague and negative. The lines and masses are reduced to a minimum. The subjects are usually small things, or large things seen in a small way. The simplicity of the mind of the artist is perceived in the simplicity of the object. Technical skill is rather avoided, and the picture gives an impression of a certain awkwardness of treatment that reveals the inner meaning of the thing painted.

pp. 89-90

Applied to poetry comics: The simplicity and directness of comics and line drawings are perfectly aligned with poetry, even more so with the “small” haiku. Comics – underground comics especially – often celebrate the honest, the real, the creative over the technical skills of the artist/poet. Words and drawing together can transcend inherent limitations of each.

The combination of haiku and haiga is perhaps the most important practical question. One may spoil the other; but in the case of a complete success, how does one help the other? There seem to be two main ways of doing this. The haiga may be an illustration of the haiku, and say the same thing in line and form; or it may have a more independent existence, and yet an even deeper connection with the poem.

p. 90

Applied to poetry comics: This aligns with what Scott McCloud lists in his classic Understanding Comics (William Morrow, 1993) as categories for “the different ways in which words and pictures can combine in comics:” Word specific (illustrative); picture specific (words add a soundtrack); duo specific (words and pictures say the same thing); additive; parallel (words and pictures follow very different courses); montage; and interdependent (“words and pictures go hand-in-hand to convey an idea that neither could convey alone”). (See pp. 152-155.) The last three are closest to what Blyth calls independent existence and can express something neither could do on their own.

Art comes down to earth; we are not transported into some fairy, unreal world of pure aesthetic please. The roughness gives it that peculiar quality of sabi without age; unfinished pictures, half-built houses, broken statuary tell the same story. It corresponds in poetry to the fact that what we wish to say is just that which escapes the words. Haiku and haiga therefore do not try to express it, and succeed in doing what they have not attempted.

p. 104

Applied to poetry comics: Comics are down-to-earth and can make even the most difficult topics accessible. Comics span decades and can still hold an audience (e.g., Peanuts). Poetry can convey difficult or sublime concepts in just a few words. Poetry too can move through generations. Words and pictures together, as in poetry comics, open up the possibility for “yet an even deeper connection.”

Timeline: Prehistory

Warning: This incomplete history maps my journey as a poet learning about comics and doesn’t follow a strict chronological order.